In Feb 2023, an official report published by the Buenos Aires city government announced the establishment of a specialized team to preserve & restore exposed art & architecture… naturally, their primary concern is Recoleta Cemetery. The original article can be found here, but below is our translation plus some additional information. Fantastic news!

A team of experts restores the sculptural heritage of Recoleta Cemetery

For the first time, the necropolis has a dedicated area and a team of professionals specializing in the preservation of heritage works exposed to the elements. This pioneering project will serve as a model for preservation in other cemeteries.

A visit to Recoleta Cemetery is an invitation to explore the origins of sculpture in Argentina. With 200 years of history, this heritage site and prominent tourist attraction houses pieces created by renowned artists. The protection of these works from the elements is undertaken by a team of experts who carry out 3D conservation and restoration work, accompanied by an audiovisual documentation plan for the artworks.

For the first time, the necropolis has a dedicated area for these tasks, overseen by restorer Miguel Crespo, a specialist in the preservation of heritage works exposed to the elements. With extensive experience behind him, the project is pioneering and aims to set a precedent that can be replicated in other cemeteries both nationally and internationally.

“Having our own restoration team is fundamental to preserving the cemetery’s sculptural heritage; it is our duty to protect it for future generations,” emphasized Julia Domeniconi, Secretary of Citizen Services and Community Management for the City of Buenos Aires, the agency that oversees the General Directorate of Cemeteries. “Year after year, we’ve noticed a steady increase in visitors, which has led the city to develop a plan that allows us to showcase all of its heritage as a central element of its international appeal,” she added.

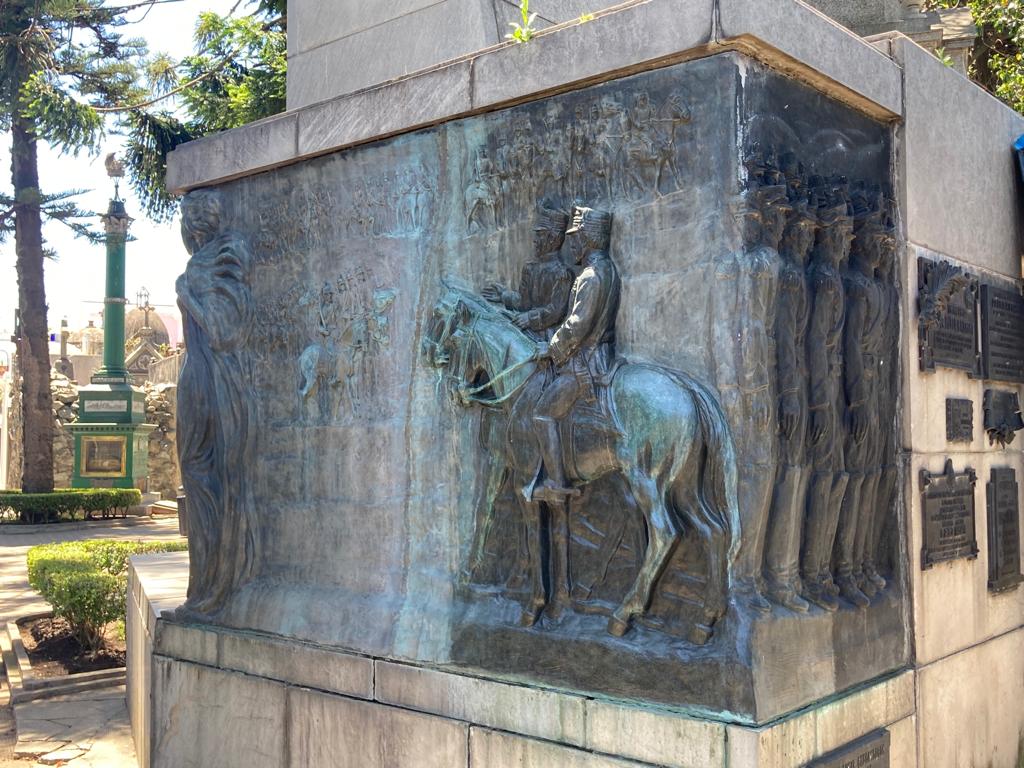

Many of the most outstanding mausoleums and funerary and sculptural pieces in Recoleta are artistic and architectural creations made between 1880 and 1930 by national sculptors such as Lola Mora, Lucio Correa Morales, Troiano Troiani, Alfredo Bigatti or Antonio Pujía, and foreigners such as Jules-Félix Coutan or Ettore Ximenes.

The cemetery’s restoration department is responsible for preserving and restoring national heritage tombs. Of the cemetery’s 5,000 vaults, 90 hold this designation, and it is estimated that 80% of the total have already undergone restoration. The team works in clusters, focusing on sites where several monuments are located together, with the aim of consolidating a notion of the work within its context and within a comprehensive plan.

“The actuality we see today in this walled space was created during a very important moment in Argentine art, that of our first sculptors. In those decades, the National Museum of Fine Arts was created, and the signatures that are in the cemetery are also in the museum,” explains Miguel Crespo, who dedicated many years to the study of outdoor art pieces through research grants from CONICET.

Although the expert’s work at the site dates back to 2002, it wasn’t until this year, after the income from entrance fees charged to foreign tourists in accordance with Law 4977 —which stipulates that the proceeds from these fees must be used exclusively for the maintenance and restoration of the historical, cultural, and architectural heritage of cemeteries— that the city’s Cemeteries and Heritage departments consolidated an institutional program with a specific restoration area for Recoleta Cemetery. “This is a fundamental event that can establish a methodology for intervention,” the area coordinator emphasizes.

Diagnosis and intervention plans

Restoration involves conducting a diagnostic assessment to determine the alterations the artworks have undergone over time. This deterioration may be due to the nature of the materials used or to changes in how the artwork is valued. Once the causes of each are identified, an intervention plan is developed for each three-dimensional piece.

The work, carried out by the team leader in coordination with restorers Paula Booth and Lorena Pacora, is done in sections. It usually begins with the fronts of the vaults, continuing with the profiles and back sections.

The works that make up the historical heritage of Recoleta are made of inorganic materials (stone/metal and imitation stone —a formulation of artificial stone native to Buenos Aires, which imitated European materials and aesthetics), mostly bronze and marble brought from Europe. The restoration, therefore, consists of cleaning and returning these materials to their original state.

In each intervention, a diagnosis of the artwork is made to identify any pathologies or alterations it may have, as part of an interdisciplinary research project on the chemical and physical reactions that affect the artwork’s support. Based on this diagnosis, the restoration plan is developed.

The deterioration of the pieces can be caused by natural or human factors. Natural factors refer to meteorological parameters such as relative humidity, rain, wind, temperature, and sunlight, while human factors stem from urban pollution or human intervention. Located in a densely populated area, the pieces are affected by urban pollutants such as carbonaceous particulate matter, sulfur, and other elements associated with pollution, vehicular traffic, or in some cases, building incinerators.

“When making the diagnosis, we have to go way back in time: the environment is more controlled today, but problems remain from construction projects. In the analysis, we see what happened decades ago, and although the environment has improved and doesn’t have the same level of pollution as before, the alterations produced at that time are still present today, and we have to remove those traces of pollution,” Crespo explains.

In the words of the cemetery’s operations manager, Sonia Del Papa Ferraro, “Recoleta’s heritage goes beyond monuments and architecture. We have to take care of the paving stones because it’s a very old site, the pipes, the basements, the effects of the foliage that grows in certain areas, the way the walls sag over time due to weight, the weather, and even the cemetery’s location in the middle of the city. The deterioration of monuments on Junín Street, which has no traffic, is not the same as that of those located on Azcuénaga Street, where the faces and bodies of the sculptures will be blackened by traffic.”

Alterations affect the artworks themselves as much as their interpretation, which is the viewer’s ability to recognize the overall composition. “These works are created using a language of harmonious contrasts, and when a crust of this particulate material forms, it produces an exaggerated contrast that distorts the interpretation. The effect on bronze is not the same as on white marble; even different works in white marble present different situations. That’s why we have to develop a specific plan for each piece,” the coordinator explains.

The effects of deterioration vary depending on the materials. During restoration, the carbonaceous particulate matter that accumulates in the concave parts of the sculptures is removed, as it alters not only the interpretation of the work but also the alloy of the material.

Proper restoration involves several aspects. “When these works were created, it was known that they would be on display, so the sculptors, the creators, had a certain level of expectation. For example, with the bronzes, the sculptor believed it was beneficial for the environment to slightly alter the patina of color that develops over time, because it enhances the three-dimensional language. So, we have to remove the alteration but preserve this essence,” the specialist points out. He adds, “In restoration, everything is important, from small to large-scale works, and in the cemetery, we have a wide variety. Some monumental restorations have included the tombs of José C. Paz and Toribio de Ayerza, created by European and Argentine sculptors, which required a great deal of work.”

Once the problem or damage caused by wind, the presence of fungi, the impact of light, or the sculpture’s position has been identified, a restoration proposal is made. “By removing the coatings, we are removing part of what time has given it, the color the artist applied, which is why we cannot carry out interventions that cause alterations,” emphasizes Lorena Pacora.

The restorers work on what is known as the black layer or crust, which is the accumulation of rain, dust and different agents that accumulate over time in the concave parts of the piece.

Laboratory, mobile workshop and digital archive

After the diagnosis, the restoration work begins in the laboratory, a workshop and heritage storage space located within the cemetery and equipped with supplies, mostly chemical, that are formulated according to the pathologies identified, for each treatment.

The work infrastructure includes tools, non-abrasive chemicals for surface treatment, scaffolding for work at height – the vaults can reach five meters high – and a mobile device known as the “Recoleto“, which facilitates the transfer of supplies and materials from the workshop to the work to be restored within the five hectares that the cemetery grounds occupy.

Tools used for removing elements that cause deterioration in stone and metal range from cotton swabs with neutral detergents to remove the surface layer of dirt from the metal during wet cleaning, to scalpels, fine-bristled toothbrushes, and paintbrushes for dry cleaning. The cleaning work is carried out in a grid pattern to visually assess whether the applied material is causing any damage to the artwork, with a step-by-step analysis.

On a workday, Lorena Pacora focuses her attention on the vault where the remains of Pablo Riccheri (1859-1936) —who served as Minister of War during Julio Argentino Roca’s second presidency —a monumental architectural and sculptural ensemble by the artist Luis Perlotti (1890-1969). The varying sheens and tones of the stones and metals reveal the progress of restoration in its different stages, divided into grids, with some sections still under intervention and others already finished.

“The chemical formulations we use are designed to control the pH in the case of marble, and other formulas with different chemicals that interact with each other to remove dirt. The goal is to avoid aggressive cleaning. We always maintain that the material must be treated with care,” Booth adds.

“After conducting small tests in different areas and determining the detergent to use, we applied it with a swab. It’s a very meticulous job that requires a lot of concentration. It’s not an invasive detergent and allows us to carefully control the process, removing the dirt. There are also areas within the same section that have a higher concentration of dirt,” adds her colleague.

“A careful cleaning must be done because it is irreversible and you can cause a loss of information in the artwork. We restore the artwork and at the same time we have to preserve everything that has been transformed over time, which is what gives the piece its temporality within a genuine intervention,” Crespo emphasizes.

The work on each monument can last for several months, as it is carried out simultaneously on multiple pieces and is accompanied by photographic and documentary documentation of each piece and intervention, with interactive information available to other researchers. “We dedicate ourselves to recording the technical aspects of each work, the resources used for the restoration, and the entire history of each monument in individual records where we can find all the references for each piece, with searches by monument, sculptor, techniques, or other data,” explains the cemetery manager.

National historical heritage: from Brandsen to Sarmiento

Among the most recent interventions are those of the burial complex where Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson (1786-1868) rests, a very old work of white marble with sculptures. Also restored are the vaults of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1811-1888), Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810-1884), Dominguito Fidel Sarmiento (the national hero’s adopted son, 1845-1866), Martín Rodríguez (creator of the Recoleta Cemetery, 1771-1845), and, among others, that of Nobel Laureate in Chemistry Federico Leloir (1906-1987).

“Beyond the fact that the criteria for declaring a tomb a national historical landmark are based on the identity of the human remains it contains, in the restoration we prioritize the artistic aspect of each monument, the sculptor, and the value of the carvings,” the director explains. “We try to ensure that the restoration speaks more to the work of the person buried there, because in doing so it will reveal what is often hidden in the cemetery: the artistic quality it holds; we know very little about who created these works and what techniques they used,” he adds.

“Our work as restorers immerses us in an atmosphere that makes us forget everything that is happening around us… Until a tourist arrives and asks you about Evita,” Paula Booth humorously shares, referring to the most visited vault in Recoleta.

Restorers warn of the need to raise awareness among visitors regarding the care of the artworks. In many cases, and due to the myths surrounding the cemetery’s history, it is not uncommon to encounter people who caress a sculpture or pose for selfies, convinced that these actions bring good luck. “The artworks should not be touched; therefore, it is a challenge to guide tourists so that they do not end up damaging the heritage,” Crespo points out.

Recoleta Cemetery also has a storage facility where donations of sculptural reliefs and other artistic pieces are kept, donated by families interested in preserving the carvings. “Some are signed works by artists whose pieces would have been lost when the tomb was moved, but thanks to the management’s efforts, they remained here. We are now beginning to build a collection that will form the basis for an interpretation center in the future,” concludes the conservation coordinator.

Update (Feb 2025): Because this project is such big news, national newspapers helped spread the word.The city government’s YouTube channel later filmed restorer Miguel Crespo in two programs of the “Oficios” (“Trades”) series:

One typographic error has been corrected, & all photos are from the original publication. Internal links to well-known mausoleums have been added for readers’ interest.

Be First to Comment