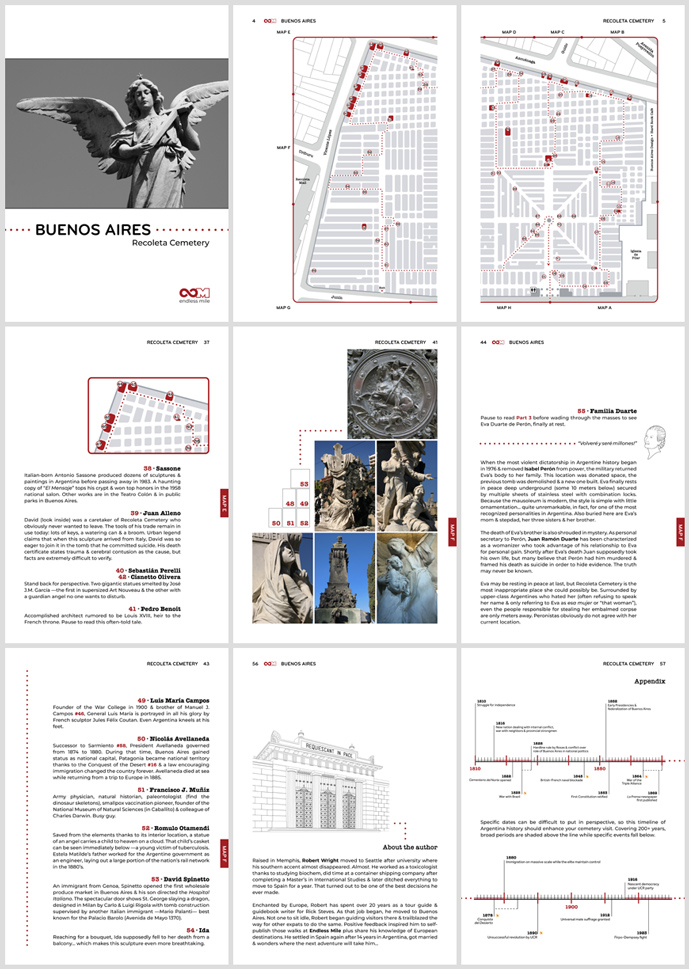

One of the most precious gifts that Recoleta Cemetery can give to any visitor is inspiration. Many visitors go without any expectations but then something speaks to them… perhaps a tale about one of its residents, the sunlight & shadows, or maybe the beautiful works of art on display. Mark wanted to share his experience with us & our readers:

My name is Mark and for the past few years I’ve been writing and performing songs under the alias M Alexander. I’m 32 and from Belfast, Ireland and my songs tend to be in the genre of piano-based rock and folk.

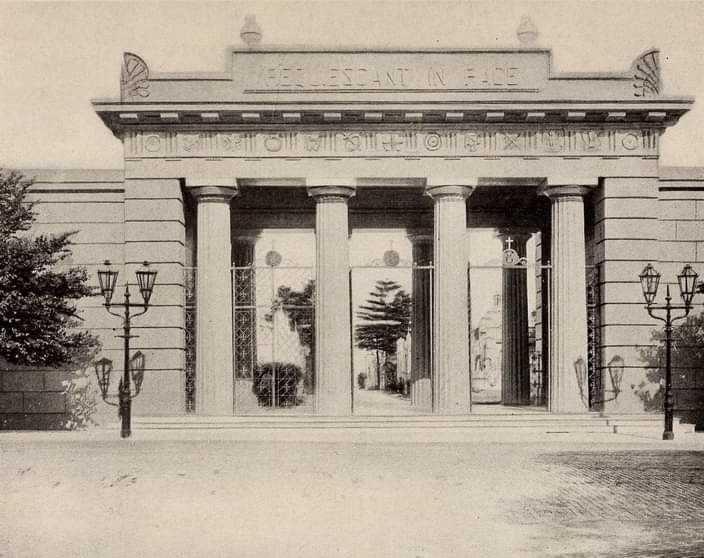

Anyway, earlier this year I visited La Recoleta cemetery for the first time. As I’m sure you will appreciate, I was absolutely ENTHRALLED by the place. We planned to go for half an hour and stayed for nearly 3!!

Simply put, I’ve never been anywhere like it. I’ve always had an affinity for graveyards, but this was next level- and it’s been stuck in my head ever since. As a result of the visit, we made a point of visiting other South American graveyards on our trip including another beautiful site in Punta Arenas, but La Recoleta definitely has a unique vibe and feel.

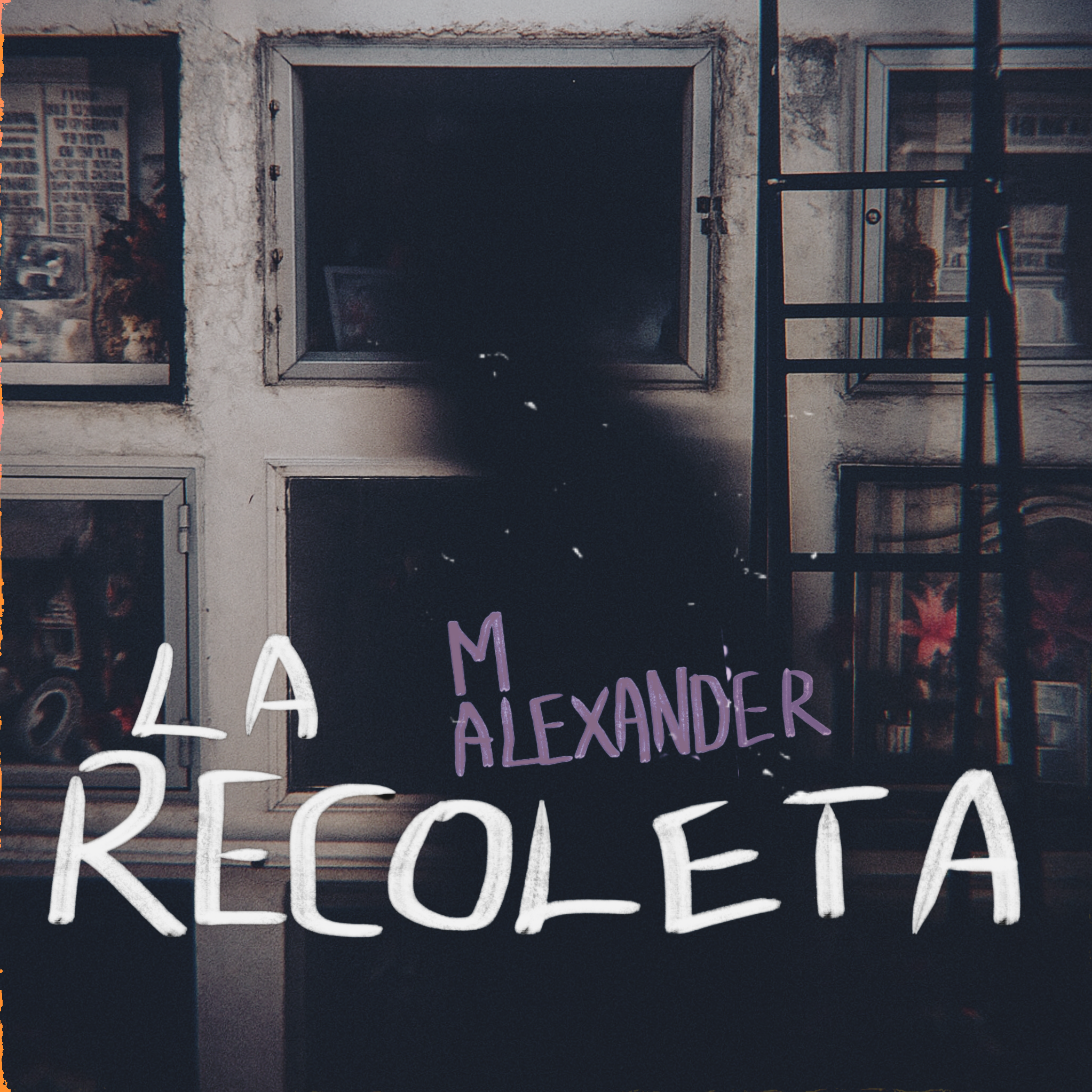

As a result of Mark’s visit, he felt the need to write a song about Recoleta Cemetery! You can imagine our thrill when we heard the stories of Juan Alleno, Tiburcia (wife of Salvador María del Carril) & of course the ever-popular Rufina Cambacérès referenced in the lyrics. Marcelo & I absolutely loved it! Released in October 2025, listen to a teaser below:

For the full version, head over to Mark’s artist page on Spotify. And keep in mind that wherever you travel, inspiration can come from the most unsuspecting place.

Leave a Comment