Years can pass without much happening in Recoleta Cemetery, but 2024 seems special with lots of research & investigations taking place. I don’t think I’ve ever had to post two newspaper articles back to back! Below is the translation of an article published on 02 Aug this year by the media outlet Infobae (original link in Spanish is here).

The vault that holds the remains of Camila O’Gorman in Recoleta Cemetery is opened for identification

Pilar O’Gorman, great-great-great grandniece of the young woman who had a deep love for the priest Uladislao Gutiérrez and who she was shot with in 1848, fights for the family vault to be declared as a historical heritage site. The poor state of the crypt, which is in danger of collapsing. And why the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Jorge García Cuerva, was present at the event.

By Hugo Martín

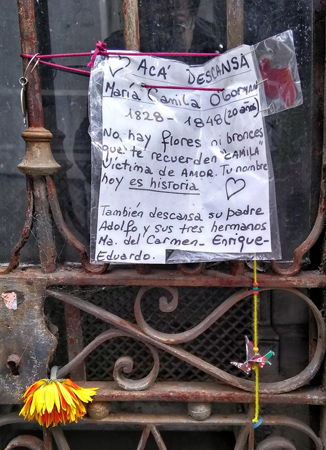

Pilar O’Gorman waits by the rickety iron door of a crypt. In her hands she holds a framed portrait of Camila O’Gorman. She is 30 years old & is her great-great-great grandniece. Seven generations ago on August 18, 1848, her predecessor, that young woman from Buenos Aires society who fell in love with the priest Uladislao Gutiérrez, was shot alongside him. The story became popular in the 1980s, when that impossible romance was made into a movie: Camila. But now it is 11:30 on the humid & gray morning of August 1st, & the setting is Recoleta Cemetery. Above the entrance to the vault it reads, verbatim: “Families of O’Gorman and Isla”. The Islas, explains Pilar, “are a family of the Buenos Aires bourgeoisie, politicians. A daughter of Enrique, Camila’s brother from whom I am descended, married an Isla.” The entrance is sealed with a padlock. Pilar says that the father of a well-known writer placed it there, he left the key with the cemetery’s administration & that it was lost. A few weeks ago they tried several, without luck. Everything is neglected: the glass on the door is broken, dirty and covered in cobwebs. Only white ribbons that people leave remain tied to the wrought-iron. As with the tomb of Felicitas Guerrero, it is a way to honor two young women who lived through a tragic love affair.

The vault opens

Ten minutes later, a cemetery employee arrives at the small dead-end street (No. 3 in Sector 9, near the entrance), which faces the wall on Junín Street, with a circular saw. He unscrews a white rosary that is attached to the padlock. He gently sets it aside. And then, with speed and precision, he takes the tool and breaks the bolt. A few sparks and the doors, crowned by a semicircular iron arch, creak open.

Inside, the deterioration in which it is found is depressing. The place is small, no more than 2 meters wide & another two meters deep. The walls are peeling, the mud bricks of the old construction have cracks. Three urns covered in dust are piled up in front. One is turned upside down: if it were in the correct position, it would collapse and the ashes it contains would be scattered. There are no candles, flowers or candelabras. All of that was looted years ago. Below, there is only one underground level, which according to Gabriel Roldán and Alan Martínez, the employees who entered, can reach up to 9 meters in depth. They detected that there are 12 “catres”, the name of the structures that support the drawers. However, they could not descend. They immediately noticed that the structure was moving. The risk of everything collapsing is visible to the naked eye . The back wall has a hole, & from another collapse on the left side, a coffin from a neighboring niche has entered into the O’Gorman vault & found crossed on the floor, about to break. Furthermore, according to the cemetery manager, Gustavo Rossi, an AYSA [the local water company] pipe, broken a few years ago, caused leaks that flooded and weakened the structural part of the crypt: “It is being fixed now.”

Inside the vault, with difficulty, covered in dust & cobwebs that stick to their blue sweater, Roldán and Martínez, illuminated by a halogen lamp, removed the urns. Another employee, Hector Cruz, wrote down the names in black ink. In the first there are four plaques, and inside, only ashes. There are those of María Teresa O’Gorman, who died on June 22, 1971; that of Paz Rodríguez de O’Gorman, who died on July 27, 1965; that of Ramona Rodríguez O’Gorman, whose death was on July 25th in the 1960s (the last number is illegible) and María de las N. de O’Gorman, who died on June 22, 1966. In the second urn —the one they removed upside down— only reads María G. de O’Gorman, RIP and a plaque says: Antonio O’Gorman 8/2/1912. The third urn contained two plaques referring to the same person: Adalberto J. O’Gorman, who died on June 9, 1938. They then removed a plaque from the shelf located above: Esther O’Gorman of Harrington, who died on September 2, 1977. And finally, the largest and heaviest urn —which they could not remove— and was located behind a piece of marble. They thought they would find remains of several ancestors, but the employees clarified that there was “a single skull .” That of Ernestina O’Gorman de Dhers, who died on May 29, 1957.

According to historian Héctor Daniel De Arriba —who accompanies Pilar O’Gorman in her fight for the family vault to be restored and valued— the last time a dead person entered this crypt was in 1984, when the mother was buried by the notary public, Rafael ‘Yuyo’ O’Gorman. Pilar began her struggle almost alone that, for now, she is winning. At least she managed to open the crypt. “This vault is shared, & the other part of the family has the ownership title. They are my dad’s cousins. The title remained in the hands of Yuyo’s children, who moved to a private cemetery. I couldn’t tell you if the children are interested in all this or not, because when the file was opened & they were notified of the opening of the vault because it is in danger of collapsing, they did not respond. The law says that if there is a danger of collapse the cemetery has to act. Then, it will notify you again. If you do not answer, the cemetery can use the vault as a place of tourist interest. I couldn’t do much else. I hope Yuyo’s children answer. In any case, I am working with [the Ministry of] Culture, with the Buenos Aires Legislature for a patronage project, for the [corresponding] arrangements and & with the Senate so that the vault is declared a historical heritage site.”

But the road will be arduous. Rossi explains that, for cemetery management, “we dictated the abandonment of the vault, the family was advised & the procedures began to fix everything, due to the danger of collapse. That entire sector is closed. Only now were we able to open it, intervene & do the corresponding studies to be able to restore it. Once the vault is consolidated and rebuilt, within four or five months, the family is advised again to see if they want to pay for the repair. If you do not pay the settlement, the vault [ownership] expires, the City government keeps it and the remains are removed. But it is not so fast, justice also has to act. “We are doing it with several vaults that are in poor condition.”

For now, Pilar knocks on all the doors she can to make her dream come true. “I think it’s good that the cemetery uses the vault as a point of tourist interest. And I work with them. For example, it was suggested to us if on August 18th, which is the date of the execution of Uladislao and Camila, we could hold an event here and tell their story. I told them yes, of course. I think it is important to work together so that their memory & name have a prominent place. They both went through their historical context & are personalities that touch us all.”

Also in the fight

However, today Pilar O’Gorman is no longer alone. With her, in the meager space of the internal street, in addition to De Arriba, her boyfriend Nicolás Laurnagaray (administrative assistant of the national Senate) & of course Rossi, were none other than the Archbishop of Buenos Aires Jorge García Cuerva; the head of advisors to the Senate, Agustina Tardieu; the general director of Cultural and Creative Development of the Ministry of Culture [of the city government], Carolina Cordero; another member of said team, Mercedes Urbonas Alvarez and the former head of the historical & artistic department of Recoleta Cemetery, Susana Gesualdi.

The presence of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires was one that attracted the most attention. Monsignor García Cuerva explained to Infobae that his interest in the topic was “absolutely personal”, unrelated to his pastoral work. “I have a degree in Church History. My thesis at the Catholic University, which I defended in 2003, was on the yellow fever epidemic of 1871, where two of Camila’s brothers were protagonists. They were Enrique O’Gorman, chief of police, and Eduardo O’Gorman, who was a priest . Both worked very hard to move the city of Buenos Aires forward during the epidemic. But also, I did my thesis in Canon Law on cemeteries and funerals. Together with other residents of the city, we formed a self-convened group in defense of the historical heritage of cemeteries. They are open-air museums & we must take care of them, defend them & value them, because those who preceded us on the path of life rest here.”

Camila and Uladislao

A brief review of the life of Camila O’Gorman should highlight the most important parts of her brief existence. She was born on July 9, 1825. She was the daughter of Adolfo O’Gorman and Joaquina Ximénez Pinto. She went to mass at the Socorro parish, where she met the Tucumán priest Uladislado Gutiérrez. A passion grew between them that they did not want to stop. On December 12, 1847 they fled the city. When they arrived in Entre Ríos they did so with a false identity: Máximo Brandier and Valentina Desean. In Goya, Corrientes, they opened a school. There, Uladislao was recognized and both were arrested. On August 15, 1848, they were housed in the barracks of [Juan Manuel de] Rosas in Santos Lugares [known as the city of San Martín today, just outside the current city limits of Buenos Aires]. Juan Manuel de Rosas, who found out late about the escape, met with Camila’s father, who asked for exemplary punishment. Under pressure, on August 18th at dawn he signed the death sentence. Not even the pleas of Rosas’s daughter Manuelita, Camila’s friend, made him change his mind. At 10 in the morning, the two were shot. They were buried together under a willow tree.

For Archbishop García Cuerva, Camila O’Gorman’s relationship with the priest Uladislao “is a historical fact that should not be analyzed in an anachronistic way, it must be analyzed according to her era, where all the emphasis was placed on the decision Rosas made, but it has not been taken into account that the entire ruling class, including the opposition ruling class that emigrated to Uruguay, the Banda Oriental, demanded exemplary measures, that they be shot, because, they said, the city of Buenos Aires was too liberal. It was mere political opportunism of the ruling class, which unanimously demanded this tragic measure that, of course, is absolutely terrifying to us. But I insist, we must not analyze history in an anachronistic way. And yes, perhaps, rescue the figure of Manuelita Rosas, who as Camila’s friend, interceded for her until the last moment.”

The historian De Arribas intervened in the talk with the prelate & added: “The concubinage of priests was common at that time. Monsignor Elortondo y Palacios, deputy & director of the National Library, had his common-law wife. It was normal. The high ecclesiastical hierarchy had servants who were their concubines. Here what was reversed is that Camila belonged to high society and went with a provincial priest, from a parish far from the center of Buenos Aires. They inverted that relationship code and aggravated it, in a sense, by leaving Buenos Aires. And with an something extra: Uladislao took the alms from the Socorro parish, something that a representative of the Vatican reported & is in its secret archives.”

The other myth of her escape and capture on June 14, 1848 in Goya, Corrientes, is that Camila was in an advanced state of pregnancy. “There is the report from Corrientes, where it appears she felt nauseous. Investigators said it was because she was pregnant. And then, well, as Monsignor says, the Unitarians applied political pressure & Rosas had to set an example of morality for women and men, & he had no choice but to punish her.”

Looking forward

When work on the vault was completed, it became clear that it will not be easy to determine in which shelf or urn Camila O’Gorman’s remains are. There is much to analyze underground in the crypt. One possibility would be to do a DNA study of the remains. As Carolina Cordero, who participated in the identification of remains of Falkland Islands soldiers, explains, “the best things to analyze are samples that are compared with direct lineage: fathers, mothers, brothers, cousins. Then, with the passing of generations, it begins to deteriorate a lot. You have to find DNA that has clean or uncontaminated genetic material, for example teeth or a femur. Furthermore, Camila had no descendants.” But nevertheless, she points out, there is something that would make her identification much easier: “If her bones are there, there are the bullet marks that Camila received when they shot her.”

Pilar drew an optimistic conclusion in the end: “We have been waiting a long time for this to happen. We expected this result, it would be difficult for Camila to be identified in a coffin, given the number of years that had passed. But having been able to open the mausoleum and for it to begin to be restored is a great step, a great vindication for Camila and Uladislao.”

The historian De Arribas —who wrote Four Priests and One Woman: Camila O’Gorman (Editorial Dunken)— agrees with Pilar: “The expectations of opening the vault were fulfilled. Afterwards, the part of identification of the coffin or urn that had Camila’s remains was not, because the vault is very deep and, due to the date of her burial, she would be at the bottom, and those that we discovered above, were from the 20th century. There’s still a big unknown. But documents say that her remains were transferred from Palermo and buried here on September 3, 1952. For me, who is not an O’Gorman, but a historian, I am satisfied that Pilar managed to open the vault in her titanic battle., because other O’Gormans have told me ‘Camila is in the past’. And the story is not in the past. It helps us learn from it. This story that has its romantic overtones, that of a 23-year old girl who leaves with a 25-year old priest and they get pregnant, is more than that, it broke with the canons of patriarchy, control, the bishopric and Rosas, of course. They were brave. And I think they are happy in heaven.”

Just after noon, when almost everyone has said goodbye to Pilar O’Gorman, the cemetery manager places a new padlock on the door. The brand is D-10. Rossi —a man surely accustomed to the dark humor of those who work in the cemeteries— cannot avoid the joke: “Now they have God’s lock.” [Sports reference here: a #10 jersey belonged to Diego Maradona, who had an important goal nicknamed “the hand of God.” So God & 10 go together.]

Update (16 Jul 2025): And the search continues… here’s a recent article from the TN website.

Be First to Comment