References to Recoleta Cemetery appear in some unexpected places, but as one of the most recognized & visited spots in Buenos Aires I’ve always been surprised at the lack of academic research about its development. Not long ago, I obtained a copy of a book titled “Una Arquitectura para la Muerte” (An Architecture for Death) published in Spain after a 1991 conference about contemporary cemeteries around the world. This large body of work compiles all the research from that conference & first became available two years later in 1993.

Recoleta Cemetery got some much-deserved space with two separate articles. The first was written by team of authors—María Rosa Cicciari, Marcelo Huernos, Rubén Lasso & Carla Wainsztok—who worked in conjunction with the Instituto Histórico de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. I’m surprised that I never heard of them since I often went to find info at the Instituto Histórico. Anyway, La muerte en el imaginario social en Buenos Aires does its best to favor the less exclusive Chacarita Cemetery but also presents quite a few interesting facts about Recoleta Cemetery that I’ve had trouble confirming exact dates or never knew…

- Funeral carriages often took a route down Calle Florida to Recoleta Cemetery so everyone could participate in mourning along the most famous street in Buenos Aires.

- Bodies were wrapped in sheets due to a lack of caskets during the yellow fever epidemic that gave birth to Chacarita Cemetery.

- The Estación Fúnebre Bermejo existed at the intersection of Calle Ecuador (formerly named Bermejo) & Avenida Corrientes to handle the transfer of the deceased by train to Chacarita, complete with offices & rooms for autopsies.

- A trolley line for Recoleta Cemetery began service in 1870, prior to the Lacroze line to Chacarita which commenced operation in 1888.

- The first cremation in Buenos Aires took place due to a cholera epidemic & became a standardized procedure in 1886.

- A 1923 city ordinance prohibited a public funeral service in Recoleta Cemetery with a later transfer of the deceased to another burial location. Evidently the social status of being buried in Recoleta Cemetery generated a few odd practices like this one.

- Home wakes continued until the early 20th century, like that of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. They state that funeral homes didn’t really catch on until 1960!

The second article—Arquitectura funeraria de Buenos Aires, La Recoleta by María Beatriz Arévalo & María del Carmen Magaz—starts with a lengthy history of cemeteries in Spanish territories & the creation of Recoleta Cemetery. The authors then group funeral architecture into trends based either on nationality (English, Italian & French) or by period (Art Nouveau, for example). AfterLife has covered most every topic discussed in the article, but one quote stood out for me… the basis for their research stemmed from a 1989 art history conference that outlined the conditions for every modern cemetery:

Por un lado pasa a ser una reducción simbólica de la ciudad, en segundo término es una galería donde la comunidad conserva la memoria de sus grandes hombres y, por último, es un ámbito donde desarrollar el arte.

On one hand it should be a symbolic reduction of the city, in second place a gallery space where the community preserves the memory of its great men and, lastly, a place for art to develop.

That happens to be the perfect response when anyone asks themselves: why would I visit a cemetery?

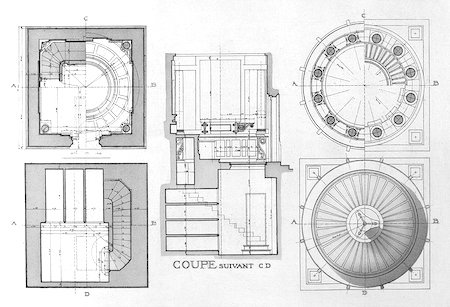

Viendo con detenimiento el plano parece ser el de la bóveda Leloir.

Sí, es de Leloir.