Written by Thomas Woodbine Hinchliff (1825-1882)—an English mountaineer, writer, founder & president of the Alpine Club—the following text was published in the book “South American sketches: or, A visit to Rio Janeiro, the Organ Mountains, La Plata, and the Paranà” [sic] in 1863. The text is in public domain, & the section which refers to Recoleta Cemetery is reproduced below.

—————————————————

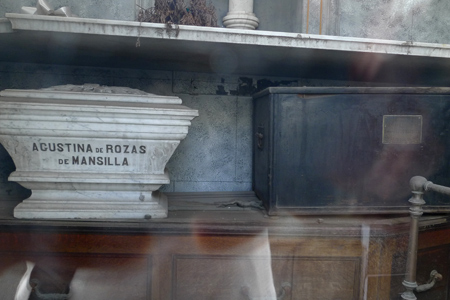

But one of the most curious and interesting places to be seen in Buenos Ayres is the Recoleta, or burying-place of the Catholics, whether natives or foreigners. It is a very large piece of ground in the northern outskirts, and is completely surrounded by a high wall pierced with loopholes, which would enable a small body of soldiers within to hold the road against an enemy. It is entered by very handsome iron gates, close to which is a chapel for the performance of the burial service. The poorer people are buried in the remoter parts of the ground, in the simple ordinary graves of Europe; but the central part is divided by numbers of paths into narrow streets of vaults and family mausoleums. The latter are for the most part built of white marble, and look like small temples, generally covered with a dome; an iron-grated door permits a view of all the coffins of the family, arranged on shelves or ledges round three sides of the interior, and decorated with immortelles and artificial flowers. Many of the principal inhabitants have spent very large sums of money upon these structures, and the general effect is remarkably good. Seen from the surrounding neighbourhood, the large collection of white cupolas and turrets, rising high above the wall, would make a visitor believe that he saw an Eastern city in the distance.

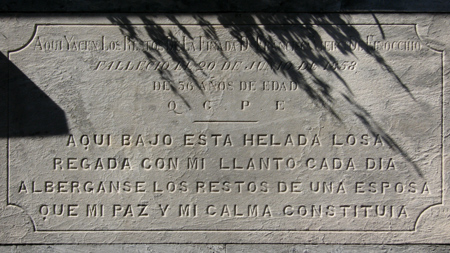

I often wandered about this Recoleta, studying the epitaphs in many languages; and one day, close to where an English Catholic had buried his wife, and graced her tombstone with the familiar ‘Affliction sore long time she bore, &c.,’ I found on a tall obelisk the most concise and terrible inscription I am acquainted with. It was this:

DON FRANCISCO ALVAREZ,

ASESINADO POR SUS AMIGOS,

1828.

‘Assassinated by his friends!’ Struck by this extraordinary epitaph I made enquiries about the subject of it, and found that a party of young men from good families of the place were in the habit of gambling together, till Alvarez won heavily from all the others. They determined to pay their debts by getting rid of their creditor, and enticing him to a lonely place the deliberately murdered him; they put his dead body in a coach that was ready, and threw it down a well in the neighbourhood. They had laid their plans so that detection seemed impossible; but by an extraordinary chance there was a witness to the crime, who denounced them. Great efforts were made by family influence to save them, but in vain; they were executed, and the brother of the murdered man erected the obelisk to his memory. In another part of the Recoleta was a dreadful hole, into which the victims of the tyranny of Rosas used to be precipitated wholesale; but those times are happily over, and no trace of them remains except in the memory of the Buenos Ayreans.

—————————————————

This text is valuable in so many ways. It gives us a first-hand account of burial practices & tomb placement of the time. Hinchliff also discusses the general appearance of Recoleta Cemetery as well as tombs which no longer exist. Finally, he makes the cemetery a tourist destination & finds an interesting story to tell. Apparently some things never change!

Entrance gate & the Iglesia de Pilar, circa 1867, shortly after Hinchliff’s visit. Photo by Benito Panunzi from the Carlos Sánchez Idiart Collection.