Born in Buenos Aires in 1877, Enrique Mosconi spent a couple of years during childhood in Europe but his family eventually returned to Argentina. After finishing elementary school, Mosconi enrolled in the national military academy & graduated at the age of 17. Typical of the era, the military was becoming more professional & Mosconi decided to study in civil engineering. Graduating in 1903, he was sent to learn about energy & communications in Europe & brought the best technology back to Argentina.

In spite of his early contributions, Mosconi would be most remembered for his next assignment beginning in 1922: General Director of Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF)… Argentina’s state-run petroleum company. Although not an expert in the field at first, Mosconi did his best to improve working conditions in Comodoro Rivadavia where the first discoveries had been made in 1907. Becoming highly influential & respected, Mosconi had the ear of President Marcelo T. de Alvear & usually received anything he requested. As a result, YPF grew as a company & demonstrated that Argentines had the capability to manage every aspect of the petroleum industry… from perforation to refinement.

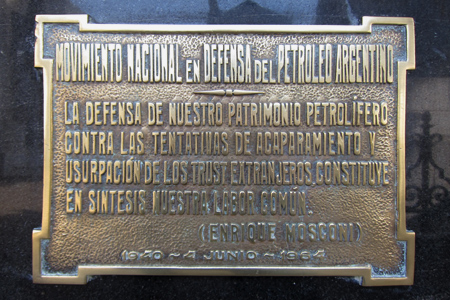

Early during his gestion, conflicts rose between Mosconi & companies such as Standard Oil & Royal Dutch Shell. He was determined to keep Argentine oil out of the hands of foreign trusts. Mosconi traveled to many countries in Latin America, where several state-run companies similar to YPF eventually formed, much to his credit. One plaque reminds visitors of Mosconi’s defiance:

A few days after the military coup which ousted President Hipólito Yrigoyen in 1930, Mosconi resigned from YPF. Several key government positions were filled with people friendly to foreign oil trusts, & some historians think the coup could have been partially supported by Mosconi’s enemies. Perhaps because of this, Mosconi disappeared from the scene. Despite a stroke which left him partially paralyzed, he traveled extensively & wrote influential books about the petroleum industry, winning many awards abroad for his ideas.

Mosconi passed away in 1940 while living with his older sisters & had only a few pesos to his name. His crypt is a wonderful monument to mid-20th century art, built with YPF funds. Although Mosconi may not have increased production to the extent he projected, he took a marginally run company & made it a source of national pride. No doubt Mosconi would have been horrified if he could have seen into the future when YPF was purchased for U$S 15 billion in 1999 by the Spanish company Repsol.