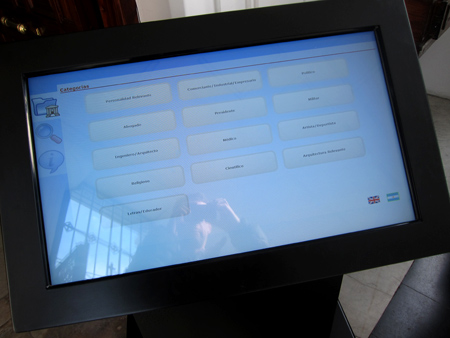

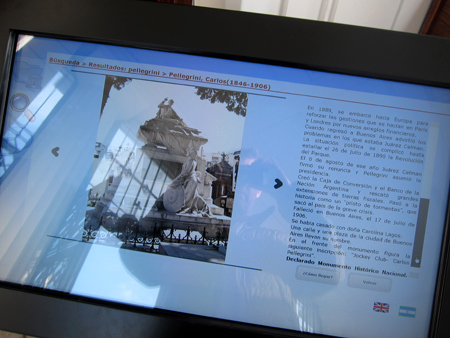

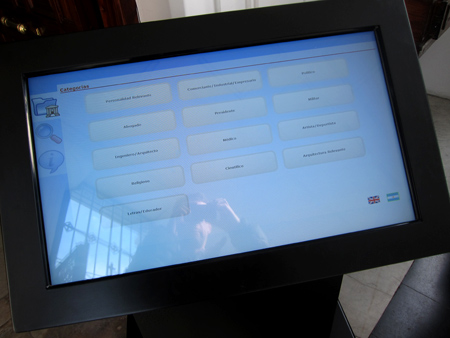

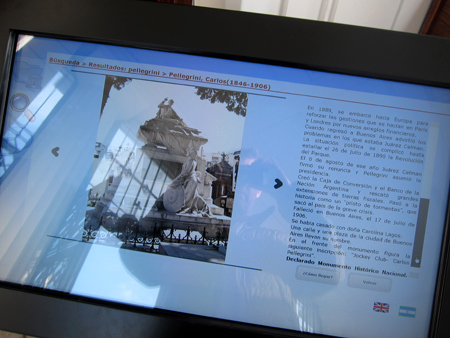

Recoleta Cemetery can now boast some of the latest technology: a touchscreen monitor with an electronic map & information about more than 200 of its most important residents. Listings are categorized mainly by occupation: President, lawyer, engineer/architect, politician, military, etc. A search function also allows users to find tombs by typing a family name. Once an entry is selected, a photo gallery & biography are displayed. Cool.

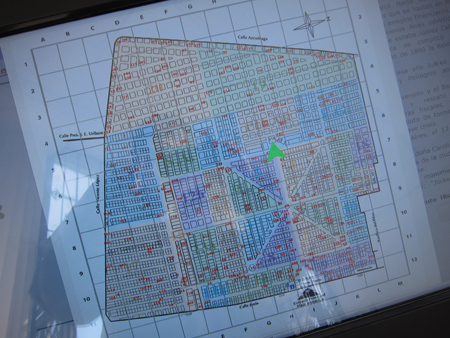

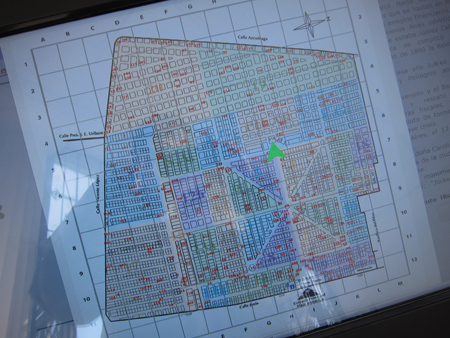

Tapping the button ¿Cómo llegar? displays a pop-up window containing a complete map of the cemetery. As if that wasn’t snazzy enough, a green arrow flashes to show the tomb location. Colored sections on the map correspond to official divisions, & all red numbers have information available… no wonder this took a year to put together!

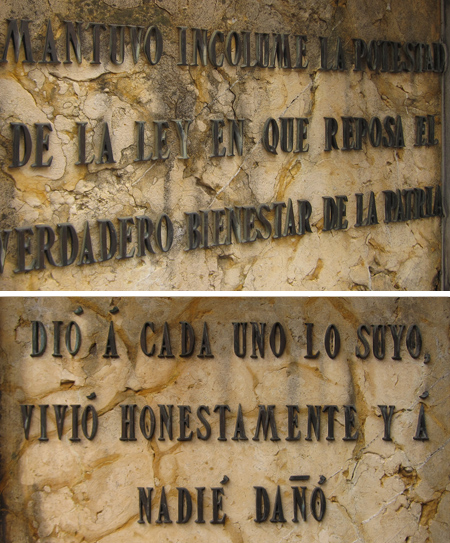

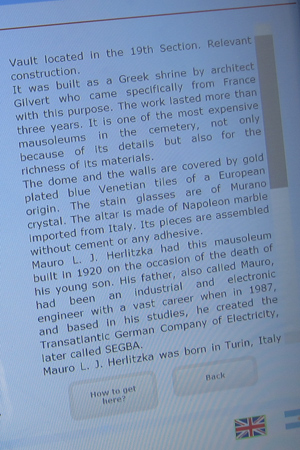

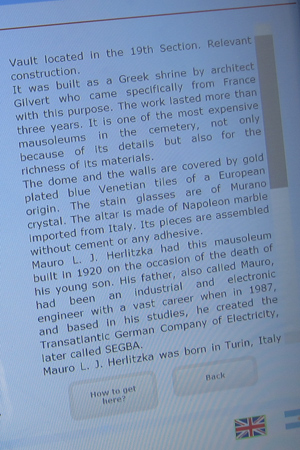

A general information section has details about guided visits plus other services, a historic background & even a bibliography. All text is available in both English & Spanish… definitely a plus for visitors. Translations could be better but all things considered, this is a great improvement over the previous lack of information in English. As an example, take a moment to read the text for the Herlitzka family vault:

Unless already familiar with the cemetery—very unlikely for the majority of people who visit—the touchscreen is more useful on the way out rather than when first entering. No print copy is provided from the search, so first-time visitors would have trouble remembering the location of any tomb not on a main walkway. Of course, they could purchase a map then spend some time marking tombs of interest. But a better way to take advantage of this resource would be to search for tombs you’ve already seen. Scroll through your digital photos, then search for info.

I know from experience how difficult it is to put together a useful guide to Recoleta Cemetery. It’s so dense with tons of history & art packed inside… any attempt at organization is overwhelming. But this is a good complement to the most visited attraction in Buenos Aires.