Hidden among a series of short rows, Ventura Coll gets little attention these days & even fewer people remember who he was. An inscription on the back side made the search for background info easier:

Thanks to some helpful people at the Province of Santa Fe historical society, I learned that Ventura Coll was a doctor there, somewhere in the province… that’s all anyone knew about his life. But Ventura’s sister, Victoria Coll, married Joaquín Marull & had a daughter named Delfina. Delfina married Ramón, so that’s how the Sardá line also wound up in Recoleta Cemetery with the Colls.

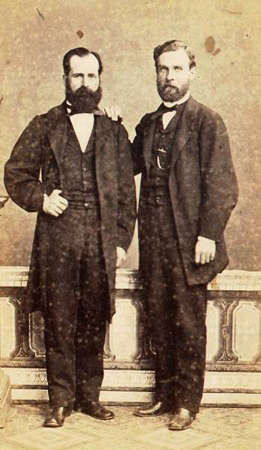

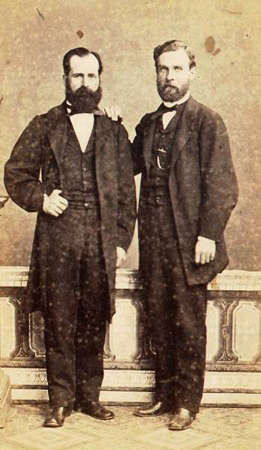

All these last names are Catalán, & Sardá was also a doctor. Seems that Coll stuck to a tight social circle of Catalan immigrants. The historical society also provided me with a wonderful photo with Ventura Coll (left) & Ramón Sardá (right). The bust on the grave is remarkably accurate:

The statue of the boy angel may seem familiar to regular readers of this blog because the same statue also decorates the Francisco Gómez family vault:

Delfina & Ramón Sardá had no children, so it’s interesting to note that they donated money to establish a maternity hospital in Buenos Aires. Opened in 1934 in the neighborhood of Parque Patricios, the building is textbook Art Deco & one of the most important public hospitals in the city. With over 6,000 births per year, no wonder it was immortalized in the 1954 movie “Mercado de Abasto” with Tita Merello & Pepe Arias: