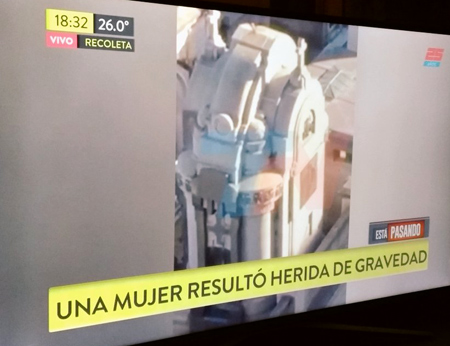

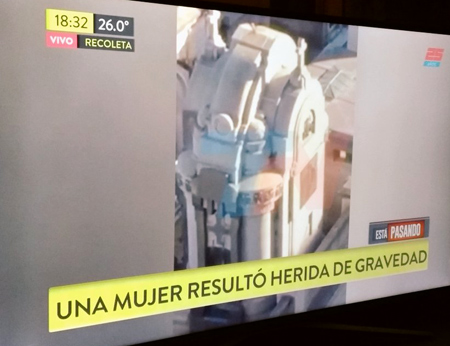

On 14 Nov 2018 around 17:15 —less than an hour before closing time— a bomb went off inside Recoleta Cemetery. Marcelo immediately sent me a message via WhatsApp & within seconds I watched the story unfold on TN’s live YouTube broadcast from my living room in Spain:

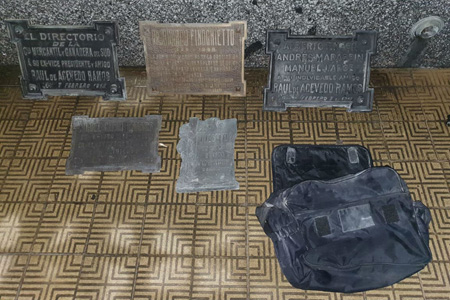

The explosion occurred in the far left corner of the cemetery at the tomb of Ramón Falcón, & initial reports mentioned one of five home-made pipe bombs exploding… severely injuring one woman who was being attended by an EMT crew onsite. Forensic police arrived to investigate the scene as well as assess any potential threat from unexploded devices. Later that day, the following photos were released via the national news agency, Télam:

The story wasn’t difficult to put together. The injured woman, 34-year old Anahí Esperanza Salcedo, had been responsible for the bombing & suffered facial damage as well as the loss of three fingers when the device exploded early… apparently while taking a selfie.

Salcedo entered the cemetery with Hugo Alberto Rodríguez, both disguised with wigs & sunglasses. They identify as anarchists & wanted to destroy the tomb of Falcón, who had been assassinated by an anarchist 109 years ago. In the end, the tomb survived while Salcedo remains in critical condition.

Police officials consider this crime linked to another pipe bomb thrown into the front patio of the home of judge Claudio Bonadio later that same day. Bonadio is currently investigating charges of bribery & money laundering involving members of the previous government, including former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. The following day federal police raided the anarchists’ base of operations in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of San Cristóbal & arrested 10 individuals after finding material used to make pipe bombs.

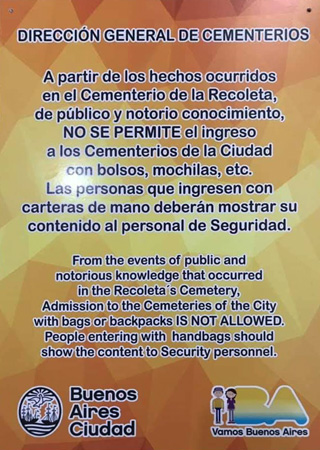

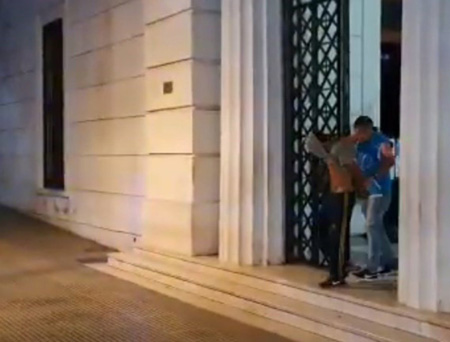

Marcelo went to Recoleta Cemetery to assess the situation two days after the bombing occurred. The first change he noticed is that bags are now being inspected at the entrance gate. While we aren’t sure if this checkpoint will become permanent, be prepared to have your belongings searched until further notice. Marcelo also confirmed the correct time of the bombing, misreported in local media as around 18:00… impossible since the cemetery promptly closes at that time every day. Forensic police were still working the scene during his visit:

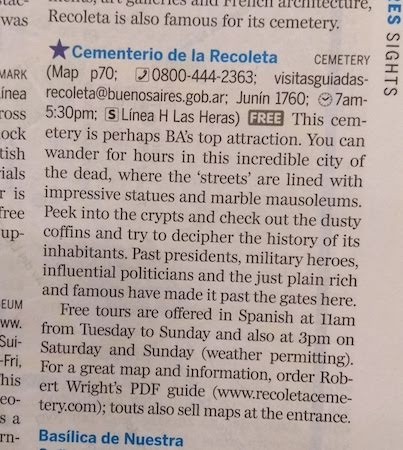

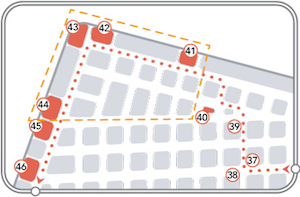

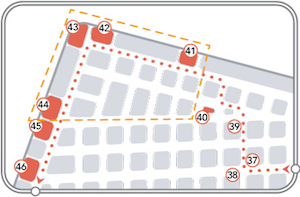

Marcelo also heard people ask in several different languages where the explosion had taken place. Word had quickly spread about the incident. He’ll return next week for an update, so stay tuned! In the meantime, tombs that are located inside the orange dashed line on the map below cannot be visited. This corresponds to locations numbered 41 to 44 in the PDF guide:

During 19 years of visiting & documenting Recoleta Cemetery, neither Marcelo nor I ever imagined this kind of violence taking place inside. Some speculate that it may be an attempt to disrupt an otherwise calm city preceding the G-20 summit. Whatever the reason, one lesson that Recoleta Cemetery demonstrates through almost 200 years of history is that violence is never the means to an end. And you can’t kill someone twice!

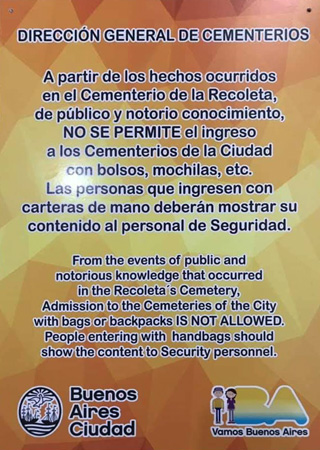

Update (22 Nov 2018): Apparently all cemeteries in Buenos Aires—Recoleta, Chacarita & Flores—will not allow visitors to enter with bags or backpacks, & handbags will be inspected by security. Photo courtesy of Susana Gesualdi: