Much remains unknown about the life of Francisco Salamone, including his birthplace. Some authors say he was born in Italy while other claim Buenos Aires as his hometown. Uncertainty even carries over to Salamone’s large body of work, scattered throughout Argentina. Fans are discovering more & more of his buildings, but here’s what we know for sure…

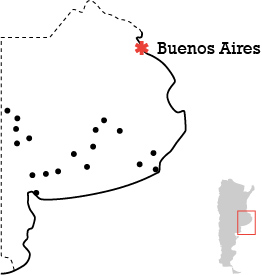

After studying architecture & engineering at several different universities in Argentina, Salamone received his degree in 1917. Through his friendship with Manuel Fresco, governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, he got a big break. Hired to design & modernize public works throughout the province, Salamone constructed over 60 buildings in his trademark style between 1936 & 1940.

Breaking through the flat grasslands of La Pampa, Salamone designed towering white structures which could be seen easily from a distance. Governor Fresco liked Mussolini—a fairly common trait in Italian descendants in Argentina in those days—and gave Salamone free reign to build something that would fit in with modern, Fascist design. The end product was futuristic, something completely unexpected in small towns seemingly in the middle of nowhere.

Salamone’s works can be divided into general categories: town halls, cemeteries & slaughterhouses. He designed other buildings as well, but those three comprised the bulk of his work. He even worked on smaller projects like benches & light fixtures for plazas.

Many have now fallen into disuse, but the rise of tourism in Argentina over the last ten years as well as an increased focus on the nation’s architectural heritage has made Salamone popular once again. Restoration projects have begun & weekend excursions go to towns that are difficult to connect using public transportation alone.

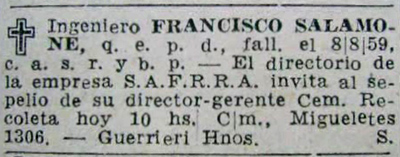

Salamone passed away in 1959 & was originally buried in Recoleta Cemetery. An obituary newspaper column announced the following:

Unfortunately, architecture buffs can no longer pay their respects in Recoleta Cemetery. After spending five years in the Lippo mausoleum, Salamone’s casket was transferred in 1964 to the López Vida family vault. But that wasn’t the end of his journey. We also discovered that he was taken to Jardín de Paz in Pilar in 1992 thanks to Rick Caba. Motives for moving around are still unknown, but all three resting places are shown below:

Salamone has been included in AfterLife due to his importance in national architecture + as one more example of a temporary Recoleta Cemetery burial.

There are a variety of online sources about the architecture of Salamone (in Spanish). With the exception of Rick Caba’s tombstone photo (used with permission), all pics are from Marcelo Metayer who administers the architect’s Flickr group. Andrés Tórtola filmed two travel documentaries about Salamone, & Edward Shaw talks about returning to the works of Salamone ten years after his first visit.

12 Comments