One of the main protagonists during the complicated birth of Argentina, Manuel Dorrego lived a life full of adventure, battles & exile with an unfortunate, untimely death.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1787, Manuel’s father was an immigrant Portuguese businessman. Dorrego’s early studies were at what’s known today as the Colegio Nacional (just off Plaza de Mayo), but when revolution began in 1810, he was studying law in Santiago de Chile. Dorrego quickly joined local forces & crossed the Andes four times bringing Chilean troops to fight the Spanish.

Dorrego’s actions got him noticed. Placed in the Ejército del Norte under the command of Manuel Belgrano, he eventually rose to the rank of Coronel & fought in the decisive battles of Tucumán & Salta. Dorrego’s bravery & skill was never questioned, but he was often insubordinate to commanding officers… both Belgrano & San Martín temporarily removed him from service.

As the conflict with Spain was being fought, another was brewing. Disagreements over the role of Buenos Aires in regional government brought Dorrego into conflict with Supreme Director Juan Martín de Pueyrredón. Arrested & sent to Santo Domingo, the ship’s crew went rogue during the voyage, Dorrego was released, & he made his way to Baltimore to meet with other Argentines forced into exile by Pueyrredón.

A change in government in 1820 allowed Dorrego to return, & his military rank was restored in order to fight again. Pushing for war against Brazil, the Federalist ideas of Dorrego allied him with Simón Bolívar. He was briefly appointed as Governor for Buenos Aires which brought him into another conflict of ideas with Martín Rodríguez & Bernardino Rivadavia. Dorrego often voiced his opinion in favor of male suffrage & economic assistance to the poor.

When the war with Brazil forced Rivadavia to resign, Dorrego became Governor of BA for the second time. He tried to annul an initial peace agreement signed under Rivadavia, continued to fight, but eventually—in part due to British economic & military pressure—was forced to accept peace. The price? Removal of all territory on the opposite bank of the Río de la Plata & the formation of Uruguay in 1828.

The loss of so much territory as well as conflicting political beliefs generated a conspiracy to remove Dorrego from power. Martín Rodríguez, Salvador del Carril, Juan Cruz Varela & many others convinced General Juan Lavalle to launch an attack against Buenos Aires. Forced to flee, Dorrego turned to Juan Manuel de Rosas who advised Dorrego to go north. Instead, Dorrego’s troops fought Lavalle & lost. Lavalle—who had fought with Dorrego in the early days of independence—ordered Dorrego’s execution by firing squad.

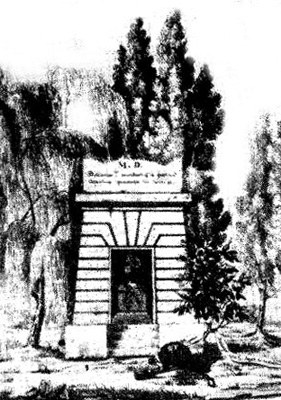

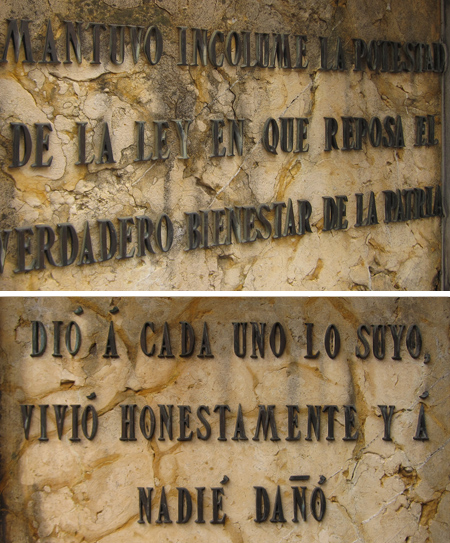

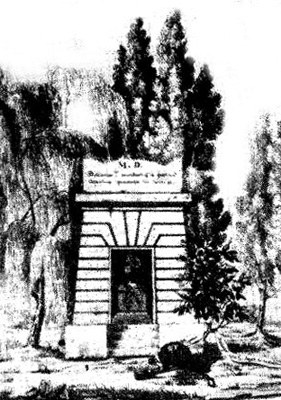

Dorrego’s sacrifice was supposed to bring an end to internal conflict but it only made matters worse. Once Rosas took control the following year, he had Dorrego’s remains moved to Recoleta Cemetery. Red flowers representing the Federalists are often found on his tomb, & an engraving shows what the early cemetery looked like at the time of his burial:

In a final letter to Estanislao López, Governor of Santa Fe, Dorrego wrote:

En este momento me intiman morir dentro de una hora. Ignoro la causa de mi muerte; pero de todos modos perdono a mis perseguidores. Cese usted por mi parte todo preparativo, y que mi muerte no sea causa de derramamiento de sangre.

In this moment I’ve been informed that I will die within the hour. I am unsure of the reason for my death; but in any case I forgive my prosecutors. Abandon any reciprocation, so that my death is not the cause of bloodshed.

This mausoleum became a National Historic Monument in 1946.