Jorge Luis Borges often wandered the walkways of Recoleta Cemetery (along with his friend & fellow writer Adolfo Bioy Casares), but his prediction of being buried there never came true. The cemetery, however, makes a remarkable appearance as the topic of one of his first published poems, La Recoleta… appearing in the 1923 collection Fervor de Buenos Aires. Below is the original text in Spanish followed by an English translation found online by Robert Mezey & Richard Barnes.

Convencidos de caducidad

por tantas nobles certidumbres del polvo,

nos demoramos y bajamos la voz

entre las lentas filas de panteones,

cuya retórica de sombra y de mármol

promete o prefigura la deseable

dignidad de haber muerto.

Made certain of impermanence

by so many noble witnesses of dust,

we linger with hushed voices

between the stately rows of mausoleums,

whose rhetoric of shade and marble

promises or foreshadows the appealing

dignity of having died.

Bellos son los sepulcros,

el desnudo latín y las trabadas fechas fatales,

la conjunción del mármol y de la flor

y las plazuelas con frescura de patio

y los muchos ayeres de a historia

hoy detenida y única.

Beautiful, these sepulchers,

the naked Latin and the linked and fatal dates,

flowers touching marble and

the little plazas cool and fresh as a courtyard,

the myriads yesterdays of a story

now cut short and unique.

Equivocamos esa paz con la muerte

y creemos anhelar nuestro fin

y anhelamos el sueño y la indiferencia.

Vibrante en las espadas y en la pasión

y dormida en la hiedra,

sólo la vida existe.

We confuse this peace with death

and we think we long for the end

when all we long for is indifference and sleep.

Vibrant in swords, tremulous in passion,

asleep in the ivy,

life is all there is.

El espacio y el tiempo son normas suyas,

son instrumentos mágicos del alma,

y cuando ésta se apague,

se apagarán con ella el espacio, el tiempo y la muerte,

como al cesar la luz

caduca el simulacro de los espejos

que ya la tarde fue apagando.

Time and space are but the forms it takes,

the magic instruments of the soul,

and when it is snuffed out,

as when the light dies

time & space will be snuffed out with it,

death will be snuffed out,

the semblance in the mirror expires,

which the twilight was already snuffing out.

Sombra benigna de los árboles,

viento con pájaros que sobre las ramas ondea,

alma que se dispersa entre otras almas,

fuera un milagro que alguna vez dejaran de ser,

milagro incomprensible,

aunque su imaginaria repetición

infame con horror nuestros días.

Kindly shade of trees,

bird-streaked wind that ripples through the branches,

soul dispersing itself into other souls,

it must have been a miracle that on a day those souls left off existing,

a miracle that passeth understanding,

even though its imagined repetition

stains our days with horror.

Estas cosas pensé en la Recoleta,

en el lugar de mi ceniza.

These thoughts came to me in La Recoleta,

in the place of my ashes.

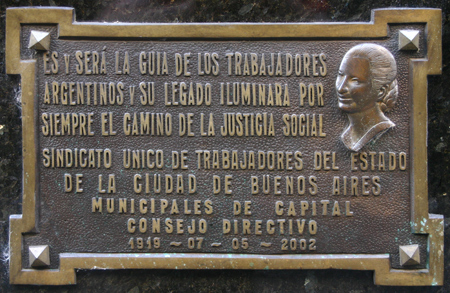

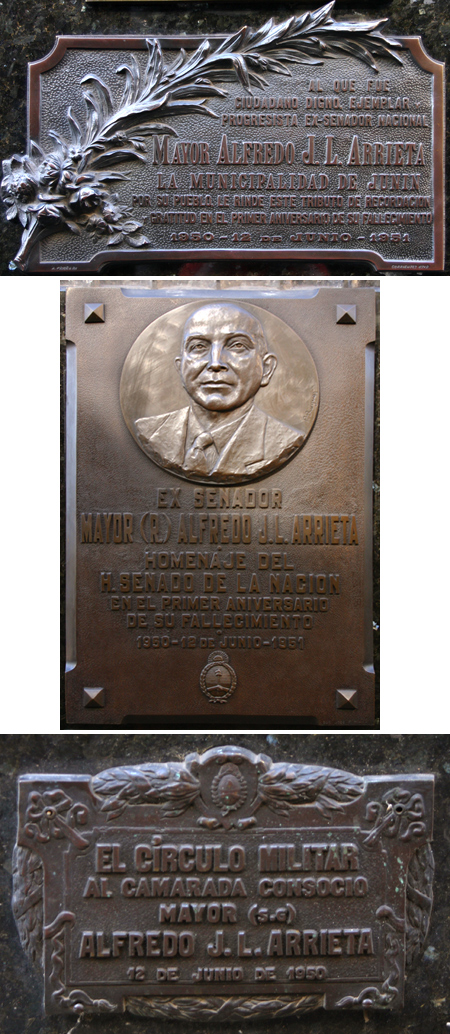

Photos courtesy of Marcelo Metayer.

Leave a Comment