No biography or other info found online. Not a single plaque on the exterior either, but one of my favorite Art Deco designs in the cemetery.

2 Comments

No biography or other info found online. Not a single plaque on the exterior either, but one of my favorite Art Deco designs in the cemetery.

2 CommentsBravery & strength are character traits commonly identified with lions. Used historically to decorate coats-of-arms of several royal families, even pop culture praises lion-like qualities in “The Wizard of Oz” & “The Lion King.” What better animal to protect loved ones during difficult times? A few large felines blend in with their domesticated relatives in Recoleta Cemetery.

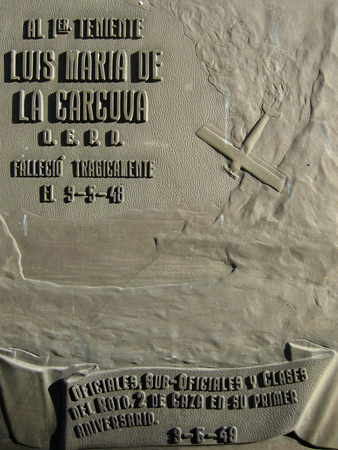

Lots of information can be found out about the occupants of a particular tomb, even with only basic Spanish… just stop & study the plaques. A picture is worth a thousand words.

Upper text reads: “To First Lieutenant Luis María de la Cárcova, RIP. He passed away tragically on 03 May 1948.” As is customary in Recoleta Cemetery, this plaque was given on the first anniversary of his death by those who miss him… in this case, fellow military personnel.

1 Comment