Lucio Victorio Mansilla was, like Ascasubi, a man whose life could have been a novel. Mansilla embodied the Romantic character: military man, writer, traveler, bon vivant.

Mansilla was born in Buenos Aires in 1831… son of Coronel Lucio Mansilla & Agustina Rozas, sister of Juan Manuel de Rosas, who they called “the star of the Federation.” As a teenager, his parents sent him on a trip to Asia, the Middle East & Europe in order to discourage a love “that was not to his convenience.” Young Lucio traveled through India, Egypt & Turkey as well as France, Italy & England. Those travels would later become material for future works of literature.

After the fall of Rosas, Mansilla’s family moved to France for a year. Lucio married his cousin, Catalina Ortiz de Rosas y Almada, after their return. He challenged José Mármol to a duel in 1856, thinking that the writer had offended his father in the novel “Amália.” The future author was exiled for three years & later sent to fight in the war against Paraguay:

In 1868 Mansilla supported Sarmiento in his bid for President, who later designated him as frontier commander in Río IV, Córdoba. From there, he embarked on a journey south to defend a peace treaty with the ranquel/rankülche tribe. Mansilla spent 18 days with them & wrote his experiences down to be published in the “La Tribuna” newspaper. His style was colloquial & included many stories, even those told by the campfire. They were published together as “A Visit to the Ranquel Indians,” one of the most striking works of Argentine literature.

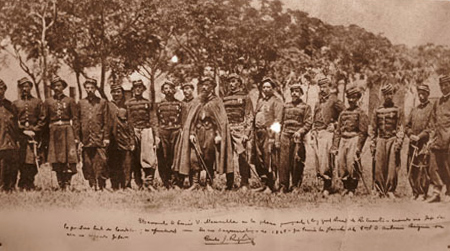

Below is an 1868 photo of Mansilla (center, wearing a cape) in what is now Plaza Roca in Río IV… two years before leaving for ranquel territory:

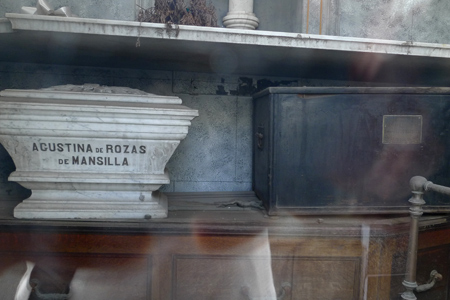

From 1876 until his 1913 death in Paris, Mansilla occupied a large number of political positions & published a number of books. But the most important experience of his life—living through & telling his time among the indigenous people of Argentina—had already passed. Mansilla rests in peace in the family vault with his mother & father, & this vault was declared a National Historic Monument in 1946:

Update (29 Aug 2012): Interestingly, David William Foster of Arizona State University considers Mansilla’s tales of the ranqueles as “one of the great classics of nineteenth-century Argentine prose, ranking perhaps only behind Sarmiento’s Facundo.” More info can be found here.

Photo of Mansilla in Río IV courtesy of the area’s Regional Historic Museum.

4 Comments

Born in Buenos Aires in 1837, Luis Huergo completed his high school education in Maryland, USA then went on to become the first civil engineer to graduate from an Argentine university. He coordinated the construction of bridges throughout the Province of Buenos Aires with British assistance, built sections of new railroad, & improved the infrastructure of a growing nation.

Although he served as a Senator in the 1870’s as well as Dean of what eventually became the Engineering faculty, Huergo is most remembered for a project he never completed: a new cargo port for Buenos Aires. He had already deepened the exit for the shallow Riachuelo, allowing transatlantic liners to enter directly. It was only natural for Huergo to be part of a design contest for the new port.

Huergo had some tough competition & an alternative plan was proposed by local merchant Eduardo Madero. Madero’s design was accepted over Huergo’s with ships entering through the southern canal, loading & unloading goods in any of four dykes, then exiting north. By the time Puerto Madero was inaugurated in 1897, it was obsolete. Madero’s design did not allow expansion of any kind… much needed when ships were growing larger & larger. Congestion was a considerable problem during Puerto Madero’s heydey with an amazing 32,000 embarkations made in 1910 alone:

To add capacity to Puerto Madero, Huergo’s design was reworked in 1907 & completed by 1919. The in-and-out design of Puerto Nuevo is more efficient & continues to function as the current port for Buenos Aires. All cruise & container ships dock there, & a gigantic plaque to Huergo highlights his biggest BA contribution:

Huergo’s son, Eduardo, also became an engineer & was responsible for the rectification of the Riachuelo. Those curves were replaced by a straight line in Eduardo beginning around 1927:

At the age of 73, Luis Huergo formed part of a national commission dedicated to petroleum exploitation in Patagonia. He advocated government control to avoid the emergence of monopolies like Standard Oil while Dr. Pedro Arata, also part of the five-member board, thought private companies would be a better option. Huergo won in the end as the commission transformed into Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales, remaining a state-run company until 1991. Huergo passed away in 1913 & left a legacy which remains apparent even 100 years after his death.

Leave a Comment

As President of the Cámara de Diputados (an equivalent to the US House of Representatives) from 1896 to 1901 —as well as brother of President Nicolás Avellaneda— Marco was decidedly not in favor of universal male suffrage & spoke out against the Ley Sáenz Peña. However, his lifetime service to Argentina in public office made him a well-known & recognized figure.

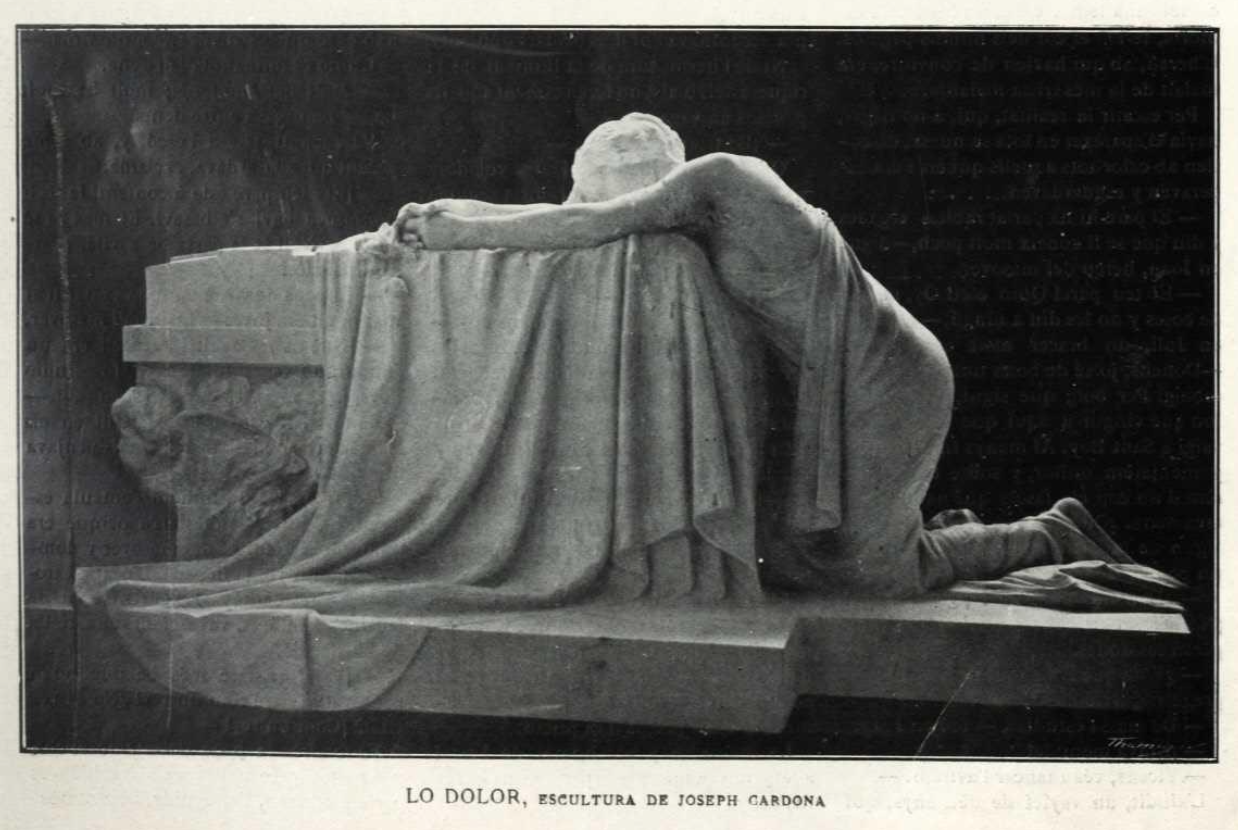

Passing away in 1911, the Art Nouveau sculpture signed “Cardona” has been admired by many… if you can find it!

Update (December 2025): Graciela Blanco has done some fantastic research into the sculpture titled “Lo Dolor” in a 1914 edition of the art magazine “Ilustració Catalana” (Year XII, Nº 596) & attributed to Joseph Cardona:

In 1909, Josep/Joseph Cardona was already a prominent artist in the Catalan community as noted by a two-page feature in the same magazine (Ilustració Catalana, Year VII, Nº 314):

In fact, praise of Cardona would continue even after sculpting the funeral monument for Marco Avellaneda (La Ilustración Artística, Year XXXI, Nº 1572):

Authors Fátima López Pérez & M. Ángles López Piqueras state that Cardona lived in Argentina from 1909 to 1918 (with a brief stay in Barcelona during 1912-13) & was warmly welcomed back to his homeland:

Returning from Argentina and after a few days in Madrid, the notable sculptor Joseph Cardona is in our city […] We give our cordial welcome to the artist, rejoicing in the triumphs achieved in America, which are ultimately triumphs for Catalonia.

However, Blanco notes that Juan José Cardona Morera —Josep Cardona’s nephew & a sculptor as well— came to Buenos Aires & lived with his uncle during the production of the funeral statue. So who was the artist? Uncle or nephew? It’s an odd puzzle with even official websites confusing the two artists.

While we may never know for certain, I’m of the belief that the uncle (who was more established in 1911) was responsible for this beautiful artwork. Blanco did compare signatures & is not convinced, but that characteristic swoop underneath the uncle’s name appears on all of his other work… however, you decide for yourself 😉

Due to heavy rains in Buenos Aires over the past week—the city received more than a normal month’s rainfall in just a few days—the entrance gate to Recoleta Cemetery suffered serious damage. Large portions of stucco crashed down last Saturday, & city engineers were on site Monday to figure out a course of repair.

Surprisingly enough, the ceiling is not made of brick like most buildings in Buenos Aires but merely a hollow, wooden frame. Architect Buschiazzo’s budget must have been tight in 1881:

Update (06 Mar 2010): It seems like city officials are taking advantage of the damage in order to make other improvements. The women’s restroom is currently gutted… perhaps a new one is on the way. For the moment, the men’s restroom is for the ladies. This is probably the only time to see the ceiling structure: