This pantheon is unique since Recoleta Cemetery does not officially commemorate national events & has very few group memorials… it’s more of a family place. The war with Paraguay ended in 1870, but the architectural style of the pantheon contains elements of Art Nouveau (popular at the beginning of the 20th century). A trip to the Archivo General de la Nación solved the dilemma. One archived photo records the site dedication in 1913:

A large statue of Argentina as female warrior (note the coat-of-arms on her breastplate) offers a branch of laurel in a gesture of peace:

Paraguay & Argentina declared independence around the same time. Stuck in the middle of South America without an exit to either ocean & no chance to develop overseas trade, Paraguay depended on its neighbors for imported European goods. As its only control mechanism, Paraguay introduced strict laws with heavy taxation & managed to earn a small fortune. Never a democracy in its early years, leadership passed from grandfather to father to son. In the 1860s (50 years after independence), Francisco Solano López was in charge. Historians still aren’t quite sure what to make of him or what really started the war, but it went very wrong for Paraguay.

Uruguay had already been created as a buffer zone between Brazil & Argentina. Both countries continued to meddle in the new nation’s affairs, & in the 1860s civil war was about to break out in Uruguay. Brazil & Argentina loosely supported one side while Paraguay supported the other. López asked permission to cross Argentine territory with troops to backup his friends in Uruguay. Argentina refused. López went ahead with his plans, attacking Brazil & occupying part of Argentina. He had gathered the largest army in Latin America, amounting from 30,000 to 80,000 troops depending on which account you read. His neighbors were no match with just a few thousand men each. López had the best odds.

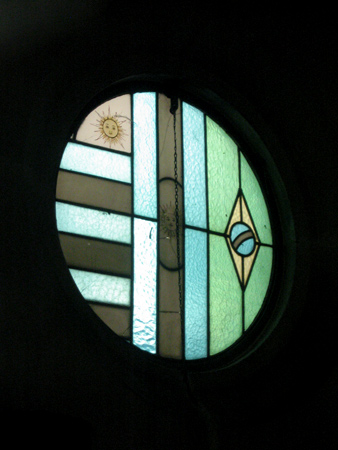

Uruguay, Argentina & Brazil decided to join forces to beat López & formed the Triple Alliance. These nations’ flags decorate the top of the mausoleum, actual flags covered in plastic are inside, & repeated again on the interior stained glass:

The 5-year war was extremely violent & eventually devasted Paraguay. They had more manpower but also out-of-date equipment & no supplies. Historical figures vary wildly, but using conservative numbers at least half of the population Paraguay was killed. In terms of gender, only 1/10 of the male population survived. When the fighting was over, López & his followers were executed & Paraguay was forced to surrender half of its territory; one chunk going to Brazil & the other to Argentina, today known as the Province of Formosa.

Revisionist historians have spent decades analyzing the facts. Was López really so arrogant to think he could defend Uruguay’s interests as well as obtain an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean? Maybe not. Someone else financed the war: England. One theory claims that since England didn’t have a steady supply of cotton from the US thanks to an equally horrible civil war at the same time, they looked elsewhere. Paraguay produces lots of cotton & perhaps the UK took that into consideration when loaning Brazil & Argentina extravagant amounts of money to fund the war. Two statues of armed soldiers remind visitors of the men who fought in one of the most horrific & often forgotten wars of Latin American history:

The pantheon became a National Historic Monument in 1983.

2 Comments