Most people eagerly say that Recoleta Cemetery was the first public burial ground in Buenos Aires. While true, much more needs to be explained. The city was founded in 1580 & Recoleta Cemetery opened in 1822, so where were its citizens buried for those missing 242 years? The answer can be found by examining traditions of Spanish Catholics who lived during that time in Buenos Aires.

When Constantine adopted Christianity, he also began the practice of burials inside the church itself. Can’t get much closer to God than that. Over time, sectors developed within the walls to differentiate the poor from the rich. Tombstones cover the floors of churches in southern Europe, & gated chapels sponsored/reserved for certain families are common. With the development of the camposanto (literally, “holy field”) located on grounds just outside the church walls, those who couldn’t afford to be inside were also given a place to rest in peace.

Allocation of church space based on wealth arrived in Buenos Aires along with the first Spanish settlers. Families aligned themselves with various religious orders to secure privileged positions. The exact spot may not have been specially marked, but families always went to a certain location for mass & knelt for prayer. Remember that Catholic churches did not have pews at that time.

A few documents from early Buenos Aires have survived & attest to a great deal of care given to funeral services. A certain amount of exhibitionism appealed to the vanity of the upper class; instructions were given for the funeral procession to follow a specific route past the residence & workplace of the deceased so everyone could say their last respects. Some people left disproportionately high sums to the church for their last rites. And the most requested spot for burial was by the fountain of holy water at the entrance… all the extra drops would land on the tomb of the deceased as a bonus. No kidding.

So who ended up where?

The poorest of the poor, if not left dead on the streets of Buenos Aires, were deposited in the Hueco de las Ánimas (loosely translated as the “pit for wandering souls”) where the Banco de la Nación now sits on Plaza de Mayo. At the opposite end of the spectrum, bishops & VIPs were buried in the crypt of the cathedral. A number of early independence figures are there as well as Virrey del Pino. Archbishops were & continue to be buried in various chapels. Guided visits are the only way to access the crypt:

Other downtown churches have their share important people. The crypt of the Iglesia de San Francisco can be found under where the main altar once stood but no public access is allowed. Approximately 200 people are buried there, mainly Franciscan monks, but former Vice President Mariano Acosta joined them. The adjacent Capilla San Roque also contains a small crypt.

Portuguese ambassador João Manoel de Figueiredo, who first recognized Argentine independence, is buried in the Iglesia de Santo Domingo. The parents of General Manuel Belgrano lie under the side stairs approaching the main altar, & the man himself is buried in the patio of the church for all to see. Prior to the large sculpture, Belgrano was buried just outside the main entrance:

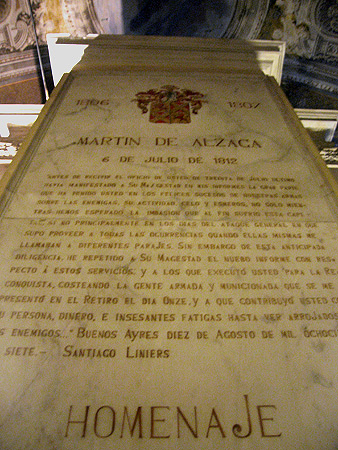

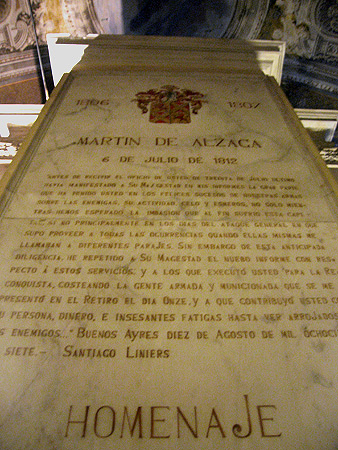

Inside the church, an homage written by Liniers to Martín de Álzaga can be found on what is supposed to be his tomb. Most likely he is in Recoleta Cemetery, but two locations other than the Iglesia de Santo Domingo claim to have the remains of Álzaga:

During the invasion of 1806, British soldiers killed in battle were buried in the Iglesia de San Juan Bautista in spite of the fact that they were not Catholic. The off-limits cloister served as a makeshift hospital so many were buried onsite.

So 242 years of burials took place in churches, & many important historical figures can be found scattered around downtown Buenos Aires. It just takes a bit of investigation to find out where they are located. Recoleta Cemetery has existed almost since Argentina became a nation… but the city’s history began much earlier.

Some content of this post from Julio Cacciatore’s Las Ciudades de los Muertos lecture on 02 May 2008.