Hidden history among the tombs of Recoleta

On weekends, hundreds of tourists visit the necropolis to see where various figures in Argentine history rest in peace

Saturday, mid-morning. Tourists line up. They are anxious because the guided tour is about to begin. A route through passageways, vaults & tombs. A walk through Argentine history via Recoleta Cemetery.

The scene repeats itself every week. According to official statistics from the city government, some 24,000 tourists visited the oldest necropolis in the city of Buenos Aires in 2008 alone.

Is it a fascination with death? Author María Rosa Lojo maintained: “Without doubt, death is the great mystery of our lives. Those figures found in tombstones, in tombs, represent us. They are our past but also our future.”

Recoleta Cemetery was the first public necropolis in the city of Buenos Aires. It was inaugurated with the name Northern Cemetery on November 17, 1822. One day later, the first people buried were a slave child, Juan Benito, and a woman named María Dolores Maciel.

Afterwards the cemetery in Flores was built in 1867 & another in Chacarita in 1871.

Guided visits consist of groups of 25-30 people, depending on the day & time. There are also organized school visits every week.

According to the city government webpage, cemetery plans were designed by the engineer Próspero Catelin, with the government reserving some plots for outstanding citizens of the nation. This act gave the cemetery its historical character.

But what is it that attracts Argentine & foreign tourists? What do visitors to the cemetery look for when they wander through its tombs & vaults?

“The founding history of the country, the first history, is found in the cemetery,” explained Carlos Francavilla, the necropolis director.

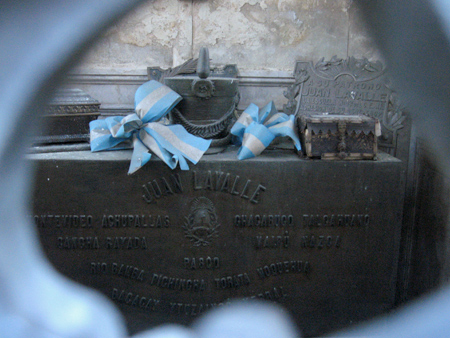

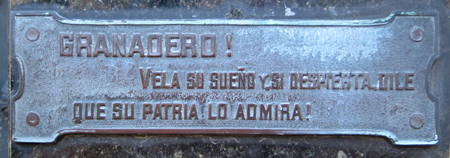

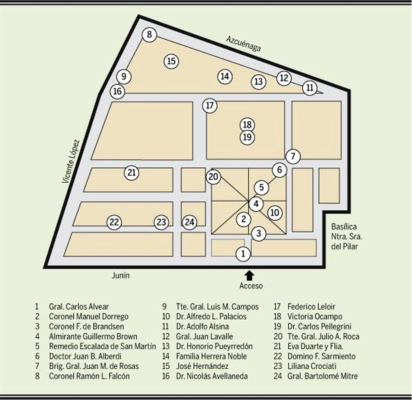

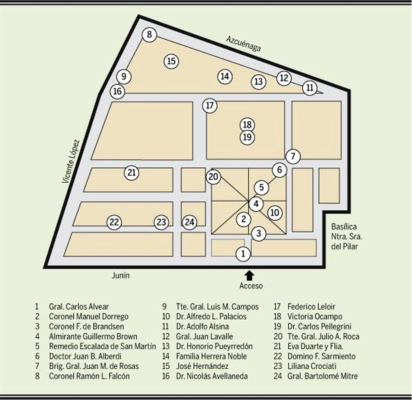

In the cemetery’s tombs & vaults lie historic figures of Argentina like Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Bartolomé Mitre, Hipólito Yrigoyen, Juan Manuel de Rosas, Remedios de Escalada de San Martín, Eva Duarte de Perón y Raúl Alfonsín, whose burial last April 2nd, was witnessed by a multitude of moved people filling the cemetery.

Not only are there political personalities buried in Recoleta Cemetery, but also Nobel Prize winner Luis Federico Leloir, boxer Luis Angel [Firpo], writers José Hernández, Miguel Cané & Marcos Sastre. Also there is a vault where María Marta García Belsunce lies, assassinated in October 2002 in her country house in Carmel.

A YouTube video originally appeared in the article but has since been removed from the newspaper’s server.

There is one vault which attracts Argentine tourists & foreigners like a magnet, especially everyone who comes from Europe. It is the vault of Evita.

“The tourist has a special interest in Evita’s vault. She is a very internationally recognized character, very popular. There are tourists who know many details of Eva Duarte’s life, mainly due to the musical,” claimed Francavilla.

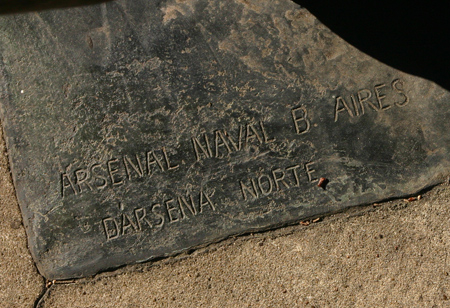

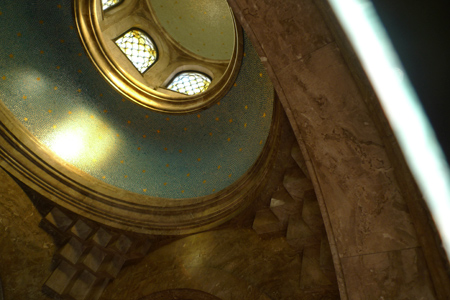

The current area [of the cemetery] is 5.5 hectares & its limits are the streets of Junín, Quintana, Vicente López & Azcuénaga. Visits are not only popular to discover those who are buried inside. It is an attraction for its architecture, expressed in distinct sculptural styles. Some 70 vaults were declared National Historic Monuments.

“The cemetery’s sculptural richness gets the tourist’s attention, so much so that they compare it with other important necropolises in the world such as the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris or the Italian necropolis of Staglieno in Genoa,” added Francavilla.

Currently, according to official information, Recoleta Cemetery does not have lot space available. Vaults were granted for eternity.

The city’s Ministry of Public Space said: “In this moment we are currently in the process of vacating a gallery of niches which were rented for 95 years. All paperwork & admin procedures for those niches which have been abandoned or unclaimed is complete. This way, the city will once again offer niches in its oldest cemetery.”

According to the rate table, 48 pesos per square meter are charged for vault maintenance per year. For enlargement of vaults, mandatory alignment with the cemetery’s layout, acquistion of vacant spaces or permission to construct underneath walkways, the charge is 84 pesos per square meter per year.

End of visit. After wandering through pathways, discovering tombs & vaults, tourists are satisfied. They feel they know more about those who sparked their curiosity.

Credits: Soledad Aznarez, Pablo Cairo, Verónica Chiaravalli, Pablo De Rosa Barlaro, Gabriel Di Nicola & Jorge Rosales

—————————

Nevermind that the article says nothing new, but errors are unforgivable. Especially with such a large group working on a single piece. Firpo’s last name was not included (!) & the cemetery in Flores was not the second built in the city… Flores was incorporated into Buenos Aires in 1888, after the Cementerio del Sur & Chacarita cemetery.

Top photo (1 of 10) credited to Pablo De Rosa Barlaro. Bold & italics not in original article.