Documenting Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires since 2007

Although the altar blocks a portion of the stained glass, this scene of Christ descending from the cross is exquisite:

And fortunately I could fit my zoom lens through the door. The glass panel is signed by Talleres Francisco Mary from 1896. They were one of the most sought-after stained glass workshops to decorate family vaults. An alternate spelling which sometimes appears is “Mari”… definitely worthy of a scavenger hunt:

While the Parravicini tomb may not be the most elaborate, Benjamín made some astonishing predictions about world events. Whether you’re a believer or not, Parravicini is recognized as Argentina’s most accomplished psychic.

Born in 1898, Parravicini was surrounded by paranormal events his whole life. But in the 1930s he began to receive messages… he compared it to someone whispering in his ear. These voices guided him in something he termed “psychographies”—sketches drawn without any conscious thought. Devoutly Catholic & horrified by his apparent gift, he destroyed many of these drawings. But quite a few survived & a large percentage have become true. Events that Parravicini predicted include the development & use of the atomic bomb, the invention of television, the Cold War & even cloning.

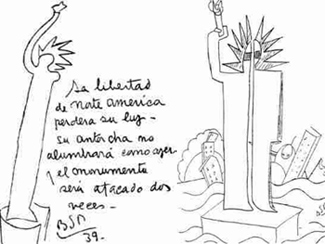

The most recent & shocking event Parravicini predicted was the destruction of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. Two of his drawings are surprisingly accurate. The first is a sketch of the Statue of Liberty dated 1939 with the following text: “The liberty of North America will lose its light. Its torch will no longer shine as it once did & the monument will be attacked two times.”

Another sketch shows a jumbled New York City skyline with the Statue of Liberty split into two separate towers. The crown appears to be an explosion. Critics would say that Parravicini wasn’t 100% accurate, but believers think that he merged the image of the Towers (not yet built) with that of the Statue of Liberty:

Intrigued? Doubtful? More biographical information & further predictions can be found here. Many of the events to come concern aliens: the discovery of an alien base on the dark side of the moon, alien visitors coming to obtain sea algae they need for food, & aliens will cure all of mankind’s diseases. It’s a much friendlier type of contact than “War of the Worlds” or “Independence Day” would have us believe.

Leave a Comment

Neglected & forgotten among the long rows of the southeast corner sits the vault for Carlos Calvo & his family. Born in Montevideo in 1822, Calvo came to Buenos Aires to study law & made a career as a diplomat for both Argentina & Paraguay. While in the service of Carlos López, father of Paraguayan dictator Francisco Solano López, an incident occurred which would shape Calvo’s career for the rest of his life.

A native Uruguayan with a British passport was arrested & found guilty of attempting to assassinate Carlos López. Calvo responded to British demands for immunity with what eventually became known as the Calvo Doctrine… any foreign resident is subject to local laws & court procedures, & diplomatic pressure from the foreign nation will be ignored as well as any attempt at armed force. Pretty gutsy. We may take this legal notion for granted today, but European powers often interfered in the affairs of the Americas during the mid-1800s. The Calvo Doctrine signified an important step for international law & a means for American nations to assert their independence.

Unfortunately no one seems to care that the Calvo vault is falling apart. In constrast to its current condition, an enormous bronze plaque pays tribute to Calvo, whose remains were brought to Recoleta Cemetery after his death in Paris in 1906. The complete text is transcribed below (errors included):

Buenos Aires Noviembre—27 de 1906—debiendo desembarcarse el día jueves—29 del corriente á las 10 a.m en el puerto de esta capital, los restos del Señor Carlos Calvo, ex-enviado extraordinario y ministro plenipotenciario de la República Argentina en Francia. Y siendo un deber del gobierno honrar la memoria de ese distinguido ciudadano por el alto puesto que ha desempeñado y los grandes servicios que ha prestado al país, el Presidente de la República en acuerdo general de los ministros, decreta:

Art 1º Por los ministerios de guerra y marina se dictarán las disposiciones necesarias para que a la llegada de los restos a esta capital y en el acto de su inhumación, se le tributen los honores militares correspondientes á General de División. En ese día la bandera nacional permanecerá a media asta en todos los edificios públicos de la Nación.

Art 2º Será de cuenta del Tesoro Nacional el entierro y el funeral del Señor Carlos Calvo, para cuyo acto se invita á los altos poderes del Estado y á las reparticiones civiles y militares de la Nación.

Art 3º Comuniquese, publiquese y dése al Registro Nacional—Figueroa Alcorta, M.A. Montes de Oca—E. Lobos, Federico Piñedo—R.M. Fraga, Onofre Betbeder, E. Ramos Mexia, Miguel Tedín

Basically, the plaque copies the text of a law which states that Calvo’s funeral expenses are covered by the national government & that he will be given a burial with full honors. Now the interior looks like this: