Born in Buenos Aires in 1815, Juan Andrés Gelly y Obes had a high-ranking diplomat & lawyer for a father. His family emigrated from Paraguay to Argentina for political reasons, & after the birth of Juan Andrés they had to move to Montevideo in 1830. Father & son fought side by side against the relentless sieges of Rosas. Those early struggles no doubt inspired Gelly y Obes to enlist in the Argentine Legion at the age of 24.

Although reaching the rank of Lt. Coronel, Montevideo would later lose all its appeal: his father moved to Brazil & his mother died after being near a grenade explosion while visiting his position. He considered joining his father & returning to Paraguay, but in the end became a politician/military man in Buenos Aires. A long friendship with Bartolomé Mitre, begun in Montevideo, influenced his career for the rest of his life.

During Mitre’s presidency, Gelly y Obes was named Minister of the Army & Navy but resigned to lead troops in person during the War of the Triple Alliance. When Argentine forces began to sack Asunción, he stepped down based on family connections there; some Paraguayans even wanted him to be their next President. In the end, he continued service in Congress in Buenos Aires & was reinstated in the military in 1877… to be removed again in 1880 after participating in a revolution with Mitre. Amazingly, this pattern would repeat itself when Julio Argentino Roca reinstated Gelly y Obes only to be dismissed again after supporting the Revolución del Parque in 1890.

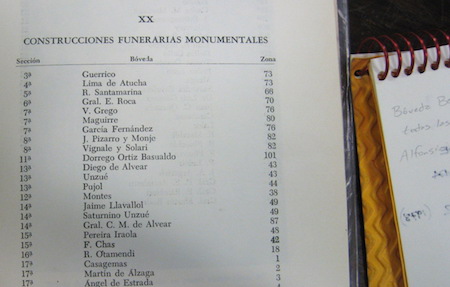

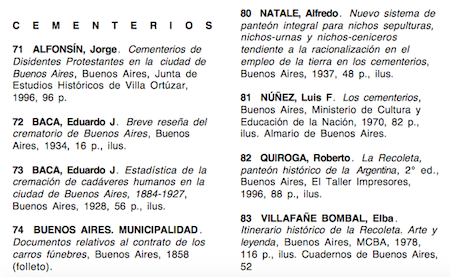

Later reinstated, Gelly y Obes served on Argentina’s top military council & supported the modernization of the military under General Pablo Riccheri. He passed away in 1904 at the age of 89 after a lifetime of service with no equal other than perhaps that of his friend Mitre! This Neogothic mausoleum sits near the rear wall of the cemetery & declared a National Historic Monument in 1946.

Leave a Comment